Denis O’Hearn, author of the biography on Bobby Sands, ‘Nothing But An Unfinished song’, is Professor of Sociology at Binghamton University, USA, and has recently been involved in campaigning for the rights of death sentenced prisoners in US Supermax Prisons. Here, he tells the story of the prisoners’ fight and their use of hunger strike:

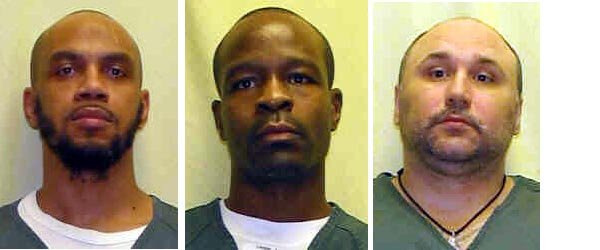

[Above: Siddique Abdullah Hasan; Bomani Shakur; Jason Robb]

INSIDE A HUNGER STRIKE

For anyone with a passing knowledge of the events in Ireland thirty years ago, the story of a recent hunger strike in Ohio will be interesting, if not downright encouraging. The history of the strike, its reasons, its beginning, and end, are told in two articles I wrote (below) that were published in the US. The first is an OpEd in the Youngstown Vindicator, the hometown paper where Ohio State Penitentiary (OSP) is located, that appeared on the day the hunger strike began and was widely reprinted in Znet and other places. The second article announces the end and victory of the hunger strike, after just two weeks, and appeared in MRZine (Monthly Review) and Counterpunch.

But before I tell the story, let me say a few words about how I became involved. I have been visiting two of the three men who were on hunger strike, for the right to be on death row! Yes, you heard right…to be on death row. Why three men should find this necessary (along with a fourth who was convinced by his comrades to stay off the protest because of his diabetes) will become clear below.

I first heard about Keith Lamar, a death-sentenced prisoner who prefers the name Bomani Shakur (Bomani is Swahili for “proud warrior”, Shakur for “thankful”), after my biography of Bobby Sands was published in 2006 (Nothing But an Unfinished Song: Bobby Sands, the Irish Hunger Striker Who Ignited a Generation, Nation Books). The legendary US civil rights activist, historian, and labor lawyer Staughton Lynd wrote to me. He’d read my book and was deeply moved by what happened in Long Kesh up to and during the hunger strike. So moved, in fact, that he wanted to use the book as the basis for a political discussion group that he was organizing among US political prisoners including Bomani Shakur and Mumia Abu Jamal. Staughton’s own book, Lucasville: the Untold Story of a Prison Uprising (soon to be republished by PM Press), was banned by Ohio State Penetentiary. So he was unsure that a book on an Irish hunger striker would be allowed in, but asked that I try. Following prison regulations, I sent copies in through Amazon. They had to be paperback.

It wasn’t long before I received my first letter from Bomani. He was a bit hesitant to contact a published author but he wanted me to know how deep an impact the story of Bobby Sands had on him. We started a correspondence and soon I found myself driving five and a half hours, each way, once a month to visit him in OSP. We were allowed five hour visits, two days in a row. I soon discovered what a remarkable man this was, who grew up in a loveless home in a ghetto of East Cleveland; whose attempts at making a reasonable life for himself were foiled time and again by a structured racism that has degenerated the lives and communities of many if not most Afro-Americans; who became a crack dealer and thief; who murdered a childhood friend in a shootout that left him first in hospital and later in prison; who was inspired by an older prisoner, a la Malcolm X, who gave him his African name; who became involved in one of the longest-running prison uprisings in US history in Lucasville, Ohio, 1993; who was condemned to death along with four others for killings in that uprising, on snitch testimony including the testimony of men who actually committed the murders; who at the time I met him had lived some fifteen years in complete isolated confinement, 23 hours a day in a cell the size of a parking space, with no human contact apart from the odd prison guard.

Bomani Shakur is also the most natural intellectual and writer I ever met. He had used his time in prison to read widely and he loved writers such as Richard Wright (Native Son, Black Boy). Somehow he learned in the process what was good writing and what was bad, and how to practice the former to remarkable effect. He was interested in Bobby Sands mainly because of his ability, and that of his comrades, to build a community under conditions of cellular isolation. He tried to do the same in Ohio, in conditions that were in many ways even more restrictive than Long Kesh. He’d had some success, despite the fact that the prisoners around him were poor raw material: apolitical, uneducated, often drug dealers like he’d been when he first came to jail. Bomani also wanted to know why he’d taken the roads he had taken, and he wanted to know how he might help other young black men to make better choices and stay out of prison…not out of committed, radical politics, just out of drug dealing and prison. He is still dealing with that, and we talk about it every time we meet.

Soon, I was also writing to Bomani’s best friend in the prison, and this most people will find hard to believe. Jason Robb is a leading member of the Aryan Brotherhood. Like Bomani, he wound up in prison for drug dealing and murder. Also like Bomani (and I have found this to be true of many other Aryan Brothers I’ve since met) his politics were decidedly to the left, with a stinging critique of US capitalism and state injustice. But his interests were different. He is a brilliant artist. He reads about the history and culture of Northern Europeans, Irish, and Greeks. He recently won a litigation against the Ohio prison system for the rights of pagans to practice their religion in the same way as Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Like Bomani, Jason was deeply moved by the story of Bobby Sands and he doesn’t mind telling you that he broke down and cried as he read about Bobby’s hunger strike and slow death. This, despite the fact that he is as tough as nails and, in Stoughton Lynd’s words, “looks like a fire plug covered in tattoos.”

A few weeks ago, my friend Jason Robb joined his brother Bomani Shakur and their comrade Siddique Abdul Hasan, a Sunni Imam and also death-sentenced after the Lucasville uprising, on a hunger strike to gain the same rights as a hundred other men on death row in Ohio. I was the first visitor to Bomani and Jason, on the third and second days of their hunger strikes. Bomani told me that he was reading the Irish political prisoners’ classic, Nor Meekly Serve My Time.

Less than two weeks later, the hunger strike ended in victory, when OSP warden David Bobby gave the prisoners a signed statement outlining agreement to the prisoners’ demands. Their insistence on a written agreement was undoubtedly informed by what happened at the end of the first Irish hunger strike of 1980. Despite a historic victory in terms of US prison practice, the struggle of the Lucasville Five, those who were death-sentenced after the 1993 Lucasville uprising, continues. As Jason Robb says, “This time around the fight was for better prison conditions. Now we begin fighting for our lives.”

Anyone interested in lending support to these men can join the Facebook group “In Solidarity with the Lucasville Uprising Prisoners on Hunger Strike” .

As Bomani Shakur often says, “It ain’t over…”

From the Youngstown Vindicator – On hunger strike, to be on death row

Monday, January 3, 2011, Special to The Vindicator

Why would anyone want to go on death row?

A federal judge from Ohio once asked that question. To be specific, he asked, “Why would anyone rather be on death row than at Ohio State Penitentiary?”

Why, indeed!

I’ve been asking myself that question since I began visiting OSP Youngstown a few years ago.

Now, the death-sentenced prisoners I visit are so desperate that they are going on hunger strike, essentially for the right to be on death row. The four hunger strikers participated in the 1993 prison rebellion in Lucasville and at least some of them saved lives by acting as negotiators with the authorities. In return, they were deemed to be prison leaders and received the death penalty for murders committed during the uprising. The evidence against them was largely testimonies of other prisoners who actually committed the murders.

Let’s leave aside the question of whether these men were guilty or, if so, whether they deserve to be executed. The question at hand is, why were they sentenced to death, yet the state of Ohio refuses to put them on death row?

The fact is that there are worse places than death row. Let me explain.

After Lucasville, the state of Ohio decided that a maximum security prison was not secure enough. They built a supermax prison, OSP Youngstown. Once they built it, they had to fill it. Today, a hundred prisoners there are kept in 23-hour lockup in a hermetically sealed environment wherein they have almost no direct contact with other living beings — human, animal, or plant. Even “outdoor” recreation is in a small enclosure with a concrete floor and walls so high that a person can see out only through the grilled ceiling overhead.

The system keeps its worst retribution for the four hunger-striking men for whom it built OSP: Siddique Abdullah Hasan, Keith Lamar, Namir Abdul Mateen, and Jason Robb. They are a strange group of prisoners. Two are Sunni Muslim. One an unaffiliated African-American. The fourth an Aryan Brother. Contrary to what we might expect, they are friends and even “best friends”. This is not supposed to happen between an Aryan Brother and an Afro-American.

Perhaps this is why prison authorities have written to them that, despite a cursory annual review of their cases, “You were admitted to OSP in May of 1998. We are of the opinion that your placement offense is so severe that you should remain at the OSP permanently or for many years regardless of your behavior while confined at the OSP.”

The lack of a reasonable review violates the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution. It also violates the explicit instruction of the Supreme Court of the United States in Austin v. Wilkinson. Moreover, keeping men in supermax isolation for long periods clearly violates the Eighth Amendment prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment.

What does this mean in real terms?

Keith Lamar, who I call by his preferred name Bomani Shakur, may be closer to me than any man on earth. I tell him things about me that no one else knows. He does the same with me. I visit him each month and when we are allowed I spend five hours with him Saturday and another five on Sunday. I love him like a brother. He is a brother to me.

Yet I have never touched Bomani, much less hugged him. One day I asked him how long it had been since he touched a tree. After he stopped laughing, he turned serious. It had been over 15 years.

Bomani told me a story about “outside exercise.” One day a leaf fell through the grille to the concrete floor below. He picked it up, hid it, and took it back to his cell. There he enjoyed this dying bit of life until a guard took it away.

Sealing men off from contact with nature, including other humans, is the cruelest punishment I can imagine.

So what would these men have if they were on death row?

On my visits to OSP I have to shout through a wall of bullet-proof glass at a man who is shackled in a small visiting cubicle. A few feet away, a man from death row sits in a booth with a small hole cut from the glass. He can hold his mother’s hand. With a little effort, he can kiss a niece or grandchild. He does not have to shout to hold a conversation.

This may not move you but consider why these men are in prison to begin with. Last year, I taught a course where my students corresponded with supermax prisoners across the US. The men wrote autobiographies. None of them pleaded innocence or for pardon; they regretted what they had done. They had one thing in common: childhoods where they were deprived of love and human contact.

If deprivation of human contact is what led these men into lives where they committed horrific deeds, why do we punish them by intensifying that deprivation? Why not give them the one thing that could have brought them from the brink in the first place: a little bit of loving, human contact? A clasp of a loving hand from time to time. The chance to show that they can be better men than they were. None of us can be hurt by this small mercy. And knowing some of these men and their capacity to contribute to society, even if their society is just a prison, we may have a lot to gain.

From MRZine – A Welcome Prison Victory at Youngstown, January 19, 2011

Three death-sentenced men were on hunger strike in Ohio State Penitentiary on January 3 to win the same rights as others on death row in the state. On Saturday January 15, the twelfth day of their protest, a crowd of supporters gathered in the parking lot by the tiny evangelical church at the entrance to the prison on the outskirts of Youngstown. They ranged from the elderly and religious to human rights supporters to members of various left groups. They were expecting to participate in the first of a series of events in coming weeks to support the men on their road to force-feeding, or even possible death. Things did not turn out as expected. For once, this was for the better.

The day’s events began when a small delegation made up of the hunger strikers’ relatives and friends (Keith Lamar’s Uncle Dwight, Siddique Hasan’s friend Brother Abdul, and Alice Lynd for Jason Robb), went up to the prison through the snow and ice to deliver an Open Letter addressed to OSP Warden David Bobby and Ohio’s state prison officials. The letter, which supported the demands of the hunger strikers, was signed by more than 1200 people including the famous (Noam Chomsky), human-rights-leaning legal experts from Ohio and around the world, prominent academics and writers, and plain garden-variety retired teachers and religious ministers. It was Saturday, so Warden Bobby was not there to meet the delegation, but he’d been aware of their coming and left someone at the front desk to take the letter.

Hopeful word of a settlement of the hunger strike had been circulating among a few friends and activists for two days. They were definitively confirmed that morning when visitors to Jason Robb received a copy of a written agreement from Warden Bobby (see below) outlining a settlement that provided practically all of their demands, despite his insistence at the beginning of the strike that he would not give in to duress.

Although the hunger strikers told me that they were optimistic from the very beginning, there were grounds to expect a harder battle. Bomani Shakur described an incident with the Deputy Warden at the beginning of his protest.

“You know, LaMar, a human being can only go so long without food,” he chided Shakur.

“Yeah, I know,” replied Bomani, “but according to the state of Ohio I’m not human, so I don’t have to worry about that!”

Nonetheless, Warden Bobby and his deputies had been meeting with the hunger strikers for some days and they agreed that they would end their protest upon receipt of the warden’s letter. Friends and relatives who came to visit Siddique Hasan and Keith Lamar (aka Bomani Shakur) told visiting friends and relatives similar details about the end of the strike. Both men said that they had resumed eating.

Shakur told one of his friends that he’d “just been eating hot-dogs.” She replied that it was crazy to eat such things on an empty stomach. Bomani just laughed and said, “but I was hungry, man!”

The delegation returned to the crowd and began the rally. The surprise was revealed to all. The hunger strike was over.

Jason Robb’s victory statement was relayed to the crowd. He wanted to thank everybody for their support, for without it the men would have won nothing. But now, he said, it was time to shift the focus to the fact that five men, including the three hunger strikers, are awaiting execution for things they did not do.

“The energy around our protest went viral,” he told Alice and Staughton Lynd on a prison visit. “This time around the fight was for better prison conditions. Now we begin fighting for our lives.”

Why a Hunger Strike?

The “Lucasville Five”, includes the three hunger strikers plus Namir Mateen, who did not join the hunger strike due to medical complications, and George Skatzes, who was transferred out of isolation at OSP after he was diagnosed with chronic depression. All five are awaiting execution for a variety of charges, mostly complicity in the murders of prisoners and a guard during the Lucasville prison uprising of 1993. In a case that resembles that of the Angola 3 in Louisiana, they have been held in solitary isolation for 23-hours a day for more than 17 years, since the evening the uprising ended. This is despite the fact that three of them helped negotiate a settlement of the uprising that undoubtedly saved lives, and despite a promise within the agreement that there would be no retribution against any of the prisoners.

The Ohio prison authorities went back on their word. They not only put the five men in isolation but they built the supermax prison at Youngstown to hold them that way in perpetuity. Having built the prison, they had to fill 500 beds, despite the fact that a small Secure Housing Unit at Lucasville had never been full. But the 1990s were the decade of the supermax. So men who were charged with minor offences found themselves locked up in Youngstown on “Level 5 security,” meaning that they were held for 23 hours a day in a cell no bigger than a city parking space. The steel-door cells and even the recreation areas where they spent an hour a day were built in such a way as to ensure that they would never have contact with another living being – human, animal, or plant. “Outdoor recreation” was in a cement-walled enclosure that was only outdoor if you consider that the roof is a steel grille. Hundreds of men have come and gone since 1998. Only four, the three hunger strikers and Namir Mateen, remain locked up in perpetual isolation.

A case is underway in the Middle District Court of Louisiana that is likely to judge this kind of treatment as a violation of the eighth amendment prohibitions on cruel and unusual punishment. It may be that the Ohio authorities see the handwriting on the wall and they want to improve the conditions of Ohio’s supermax before they are forced to do so by another court ruling, like the Wilkinson vs Austin case of 2005 in which the US Supreme Court forced them to improve conditions in the supermax.

One of the holdings of the Supreme Court instructed the Ohio authorities to follow Fifth Amendment provision on due process. In 2000, two years after the supermax opened, they began giving annual reviews to the death-sentenced Lucasville prisoners. But the reviews are not meaningful. One of the reviews even concluded, “You were admitted to OSP in May of 1998. We are of the opinion that your placement offense is so severe that you should remain at the OSP permanently or for many years regardless of your behavior while confined at the OSP.” Thus, the four have been condemned to de facto permanent isolation.

This lack of meaningful review, as well as the continued lack of human contact despite the agreement that ended the Youngstown hunger strike, might yet be the focus of litigation not just in Ohio but in other supermaxes around the United States, such as California’s notorious “Secure Housing Unit” at Pelican Bay State Prison.

The conditions of supermax are a running sore on the US human rights record, a sort of elephant in the bedroom that few people want to talk about. Yet there is a growing sentiment among experts and policymakers against extreme isolation, both because of its cost but also due to the judgment that it is a form of torture.

And it is these conditions of extreme isolation, without hope of ever touching a fellow human apart from a prison guard that drove these men to the ultimate protest of hunger strike. As Bomani Shakur wrote in a statement that announced his hunger strike, none of the men wanted to die. But in such conditions of isolation, and in the absence of any way of proving to the authorities that they were not a security risk if allowed to mix with other prisoners or have semi-contact visits, depriving themselves of food was the only non-violent means of protest that remained for them.

What Now?

For the Lucasville Five, the main attention turns now to their wrongful convictions and to the death penalty itself. Ohio is the only state in the US that executed more men in 2010 than in 2009. And it is second only to Texas in its rate of executions. For the past two years, the state has attempted to execute one man a month, although that attempt has been slowed by botched executions and by some surprising grants of clemency by former governor Ted Strickland. One can only hope that moves away from the use of the death penalty in states like New Mexico and, most recently, Illinois, are the beginning of a more general move to do away with this backward policy.

The hunger strikers expressed their hopes, to relatives and other visitors, that the energy that built up around supporting their recent protest could now be turned toward getting them off of their death sentences and allowing them to prove their innocence. Ironically, the improved conditions that they won through hunger strike could help in this regard. Among their demands – increased time outside of their cells, semi-contact visits, and equal access to commissary – was the demand that they be allowed to access legal databases like other death-sentenced prisoners, so that they could work toward their appeals.

For now, this is most important to Bomani Shakur. In a shocking recent decision, a district court judge affirmed the recommendation of the magistrate against his petition for habeas corpus without any discussion of the merits of the judgment. Shakur believes that the judge made this rash seemingly judgment in retaliation for his role in the hunger strike. Whether he has reason to believe this or not, he and his counsel now have to turn to the Federal Court of Appeals 6th Circuit. In real terms, what seemed to have been a further process of five years to execution now seems to have been shortened to perhaps three. The US judicial system is strongly biased against appeal, even in most egregious cases of injustice. So the Lucasville Five now have a hard case to argue. It is a case where public opinion and social movement may have more impact than the law, just as public pressure seems to have played a decisive role in winning a successful end to the hunger strike after such a short period.

Bomani Shakur told Alice and Staughton Lynd that the denial of his habeas petition by the district court makes him more determined and focused on what he needs to do in the next few years. Activists and supporters in Ohio and beyond will be asked to find the same kind of focus.