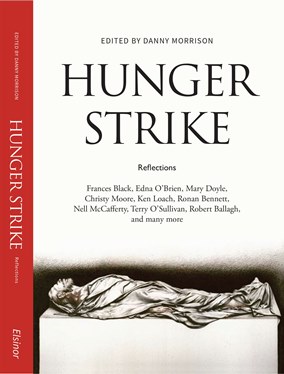

Writer and playwright Phil Mac Giolla Bháin reviews Hunger Strike – Reflections (now in its third print since its release last August). The book is available through Easons, Waterstones, most independent bookshops and can be ordered online here

-oo0oo-

IT IS MY SETTLED VIEW that it would be impossible to understand contemporary Irish politics without knowing of the seminal events during the prison protests during the Northern War.

The rise of Sinn Féin as a major political force across the island and the very real prospect of a winnable border poll in the next few years can all be traced back to battle of wills in the H-Blocks.

This was the battlefield where the British securocrats believed that they could break the IRA.

This book is an invaluable guide to the struggle of Irish republican POWs to assert the legitimacy of their struggle.

This book was first published in 2006, twenty five years after the hunger strikes had ended.

I think there has been sufficient passage of time since publication to look back afresh at the hunger strikes and their significance.

This updated edition has new chapters from George Stagg, Frances Black, Colm Scullion, Terry O’Sullivan, Trisha Ziff, Micheál Mac Donncha, Michelle Gildernew and Owen Carron.

The breadth of contributions from activists, artists and academics is impressive.

Like any anthology it can be dipped into at will or read cover to cover.

The one chapter that is non-negotiable is the introduction by editor Danny Morrison.

Through his role as Sinn Féin’s publicity director and voice of the POWs to the outside world means that he is perfectly positioned to give an overview on the hunger strike.

Consequently, I made a deal with myself when I sat down to read the new edition for this review that I would pick a trio of chapters out of the sixty two.

“For you, Frank” by George Stagg tells the incredible lengths that the Free State government of the 1970s was prepared to go to prevent Volunteer Frank Stagg being honoured by his comrades and family.

For those who did not live through those days this chapter alone will be an eye opener.

Smuggling the comms by Marie Moore reminds the reader of the centrality of women to any liberation struggle.

The British believed that they had built an escape-proof prison.

The British believed that they had built an escape-proof prison.

Of course, their imperialist hubris was misplaced and that was served up to them in the Great Escape in ’83.

The ability of the POWs to communicate privately with family and the movement outside was vital to their morale and to future operations.

Maire produces one of the best quotes in the entire book. It is as valuable as it is brief and, indeed, it could have been written with biro refill onto flimsy cigarette paper.

Here it is:

“We lost ten brave men in ’81. But the British lost the argument, and ultimately lost the conquest.”

The final chapter that I will mention is by the writer Timothy O’Grady.

1973, 1981, 1991, 2005 is a brilliant travelogue from Gola island off the coast of Dún na nGall to the reinvigorated Béal Feirste breaking free of the British monoculture that had been ruthlessly imposed by the partition statelet.

His final date on his journey has him in West Belfast for the Féile.

“Ex-prisoners were exhibiting their paintings, giving lectures, reading poems and completing their degrees. People were ordering lunch in Irish on the Falls Road.”

In referencing “lectures” and “degrees” he points to the fact that Long Kesh was very much the Frongoch of the North – a university of revolution.

O’Grady states that the hunger strike “…transformed the nature of the conflict…”

Among other things he contends is that it created, “Sinn Féin’s un-ignorable presence”.

His final paragraph notes the legacy of the hunger strikers: “…a new and growing sense of power by those who had so long been quarantined and kicked around, are the direct consequences of the dying hunger strikers placing themselves before the electorate.

“They acted, as Gerry Adams said, in the service not of death, but of life.”

I firmly believe that people do not change much, but generations do.

The prison protests got to the stage of crisis, in part, because RTE’s Section 31 shut off any serious scrutiny in the Twenty Six Counties.

The entire subject of what Britain was doing to republican POWs was largely a No-Go area for journalists, although there were honourable exceptions like Tim Pat Coogan. Indeed, I first saw the iconic image on the cover of this book on Coogan’s work On the Blanket, The H Block Story.

In the passing of time Irish people will look back on the hunger strikers and see them in the same light as the signatories of the Easter Proclamation.

That will not happen overnight.

It is a process of education, reflection and re-evaluation.

This book is a vital part of that process.

Phil Mac Giolla Bháin, is an author, blogger, journalist and playwright based in County Donegal. He is an active member of the National Union of Journalists and is the author of five books.