“Accounts of many escapes from Irish jails have been written – yet more books are still eagerly sought from which to learn more of the deeds of IRA prisoners. In truth, until this book,” writes guest reviewer, Gerry O’Hare, “I had only heard verbally anything about the escape attempts made by Danny Donnelly, from Omagh, and Belfast’s John Kelly, from Crumlin Road Jail (in 1960 during ‘Operation Harvest’).” Review continues…

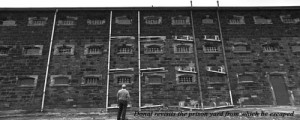

Eamonn Boyce’s ‘The Insider’, and its account of jail breaks of that time, was reviewed earlier.This is the definitive account of Danny Donnelly’s successful escape from the Crum in 1960 – and of the heartbreak and failure of North Belfast’s John Kelly, who didn’t quite make it. It is a story of two men’s attempts to overcome the odds against them by their jailers and – not unsurprisingly – the disapproval of some of their comrades.

Donnelly and Kelly didn’t inform the IRA’s jail council for fear permission would be refused them.

In a tribute to his comrade, Danny dedicates the book to the late John Kelly who died in 2007. The dedication also praises the Kelly family who lived in the shadow of Crumlin Road Jail, in Adela Street, which runs between the Crumlin and Antrim Roads.

When Kelly’s mother died, there was a Belfast silent tribute paid to her. It was said, “She never locked her back door”. IRA men on the run would understand and nod approval. Practically every prisoner who was ever released found their way to Mrs Kelly for breakfast and onward help home.

‘Prisoner 1082, Escape From Crumlin Road – Europe’s Alcatraz’ relives the story of the preparations and escape of Danny Donnelly, an 18-year-old student from Omagh, County Tyrone, convicted of IRA membership in 1957 and sentenced to ten years. We learn that he came from a family steeped in the Gaelic tradition and republicanism.

Born on September 8th 1939, he was the youngest of six children of Peter and Margaret Donnelly (nee Docherty) in a part of Omagh known colloquially as Gallows Hill.

His education was at the hands of the Christian Brothers, mostly from the South, and they would have appeared to install in the young student a love for his country and a yearning for its freedom from the British.

He tells us that growing up in Omagh gave him a sense of being a stranger in his own country. Discrimination was rampant. Catholics had no chance of a job in the town or even with the local county council. His brothers all emigrated except himself: “I went to jail,” he says.

This, of course, was not uncommon for Catholics in the six northern counties.

“We grew up in an atmosphere of disengagement from the organs of the state – from the Bureau of Employment to the local council to the police force. From an early age I wondered why people accepted these unfair conditions. I felt that things must change or be made to change. Such an opportunity seemed to present itself in the early 1950s,” he writes.

Donnelly seems to have been fascinated by the results of British elections and the successes of Tom Mitchell and Philip Clarke. He was outraged at the way the British unseated them, despite the people’s votes. It wasn’t long before he joined the IRA and came under the tutelage of Cork’s Daithi O’Connell. He learned the art of bomb-making and tells us that he became “rather adept” at it. He was also, along with the other local volunteers, taught to use Lee Enfield rifles and the Thompson sub-machine gun. It was the era of the Flying Columns around which ‘Operation Harvest’ was planned.

It began on December 12th and Donnelly’s first taste of action involved an attack on Omagh Barracks. Some of his group went off to commandeer a lorry but, as he and others lay in a ditch, they heard an explosion and, a short time later, another. The column was told that the lorry hadn’t been commandeered as planned and their anticipated element of surprise was gone. They were advised to disperse and head for home in Omagh (others headed further up the Sperrin Mountains).

The following day’s papers were full of other, more successful, operations: the blowing up of Magherafelt Courthouse in County Derry; a ‘B’ Special hall in Newry destroyed; a British Army territorial building blown up in Enniskillen and two bridges blown up in other parts of County Fermanagh.

The young Donnelly’s activities became known to the Special Branch and eventually he was arrested and given ten years for membership of the IRA. He was charged along with ten others from the Omagh districts. The jury took five minutes to convict him and sentence was duly handed down. He had expected four or five years.

Lord Chief Justice Mc Dermot, however, singled him out from the rest of his comrades and said, in passing sentence: “It is quite clear to me that you are one of the ring leaders. Parliament has made provision that the manner in which accused like you may be punished includes, not only long terms of imprisonment and whipping, but the sentence of death”.

Danny says of this tirade: “I listened with growing incredulity as he sentenced me to ten years”.

He finds jail life a culture shock, but knuckles down and continues his studies which will stand by him in later life. Escape was on his mind from the beginning and increased when he heard of the escape from the Curragh by Daithi O’Connell and Ruairi O Bradaigh in December 1958.

“Since my imprisonment, I had dreamed of escaping. On smoggy days I wondered if I could climb the outer wall during periods when the warders would count and re-count, to establish if anyone was missing”.

A decision by his jailers to build a higher wall actually hastened those plans.

“The missing part of my jigsaw … was put in place when the authorities raised the low link-wall (from the administration block to the outer wall) to the same level as the outer wall”.

Having found a weak link in the system, he realized he needed a companion and, in the summer of 1960, found a Belfast man to fit the bill. John Kelly instantly warmed to the idea, and so the plan was hatched. An extra bonus was that John’s cell was immediately above his own. Their idea was to cut through the bars of the cell to access a yard where the wall was nearest to the main Crumlin Road, giving them a starting point that allowed a restricted choice of timing.

Next, they needed a rope, 70-feet long, to stretch from an anchored spot on the administration block across the new link-wall and down the outer wall, which they estimated at 30 feet high.

“The challenge here was that, at a certain spot on the link-wall, and for the last ten yards, we would be in full view of the armed police in the gun towers while crossing. Therefore we planned to be less than ten seconds on that part of the wall so that, even if we were spotted, the chances of them taking up their weapons and firing in that space of time were fairly remote”.

Christmas Eve was set as the escape date, the logic being that Belfast would be so full of shoppers it would be difficult for the police and soldiers to spot them. Also Christmas-time within the jail was a bit more relaxed, especially for the warders.

“As a 21-year old, I also had a romantic historical reason for choosing the date as it was on Christmas Eve that Red Hugh O’Donnell escaped from Dublin Castle in 1592.”

We learn how they acquired their rope and hacksaw blades. It was John’s job to get the material and Danny’s to find the hiding places. There follows a detailed account of the trials and tribulations of their attempts to prepare for the escape – nothing’s ever that easy!

Events led to them having to postpone the escape until Boxing Day. Both men got out of John’s cell and made it to the wall. Danny gets to the top – but the rope breaks, and John falls back into the prison area. They had agreed a plan in case they were separated and, in driving snow, Danny is disappointed there is no outside help. Unfamiliar with the locality, he manages to heed John’s directions and finds himself outside the Kelly home where the door is opened by a young Oliver Kelly.

“Come on in,” he says, as if escaped prisoners are the norm at their door!

Danny says, “The Kellys were highly respected within their own neighbourhood, by churchmen in Belfast and among the business community with whom they worked on a daily basis.

“Internees and released prisoners had a standing invitation to go directly to their house, where they would receive a great welcome, a meal, good advice, directions or lifts to bus and train stations and, on many occasions, money.

“The Kelly household was revered in republican circles not only throughout the North but among many in the South also.”

In excellent hands, he makes good his escape across the border.

It was not all without pain for Danny. He suffered serious injuries to his foot and vertebrae which took a long time to heal. Nevertheless, he reported back to GHQ and eventually met the then Chief of Staff, Ruairi O’Bradaigh, and Mick Ryan.

The final phase of his book concerns how he sought work and continued his business studies.

It is a remarkable tale of success leading to his selection as Honorary Secretary of the Council of the Institute of Purchasing and Materials Management in the Republic and later, on two occasions, President of the Institute.

He drifts away from his active involvement in the IRA gets married and has a family. That he took such a long time before he got down to writing the book is explained through his concern about the direction the IRA took, leading to the long, armed campaign from the ’70s to the ’90s. He blames the British for not acting earlier to promote a just society, and I leave readers with his explanation for not remaining involved.

“I avoided being personally involved in the physical conflict by chance and, to a certain extent, through having other commitments.

“Thus I never rejoined the IRA as many of my Crumlin Road comrades did at that crucial time, nor was I part of the bitter Provisional/Official split. I knew many on both sides, and still meet with some of them from time to time. However, I was, quite frankly, appalled at the ruthlessness with which those feuds were carried out and the business that informed them.

“I consider myself quite fortunate to have been outside all that.”

The book is important as this escape seemed until now to have disappeared off the map.

Historians and the ordinary reader will be grateful to the author for telling his story.

‘Prisoner 1082 – Escape From Crumlin Road’ by Dónal Donnelly, published by The Collins Press, Price: £11.99/€12.99