Irish-American writer Tim O’Grady reviews the recently published book by An Fhuiseog, The Comrades, tributes to the hunger strikers by former prisoners, which is on sale through republican outlets in Dublin and Belfast.

-oo0oo-

IT IS DIFFICULT to approach this book as a commentator, difficult not to feel intrusive, unqualified. Everyone in it, the writers and their subjects, lay their lives on the line. The twelve hunger strikers lost theirs, as did many others mentioned. They are all a breed apart. Maybe they were themselves extraordinary, maybe it was their time. Maybe and most likely both. Their nerve, their will, modesty and unity of purpose are not quite imaginable to one who was not there and did not do as they did. They are beyond.

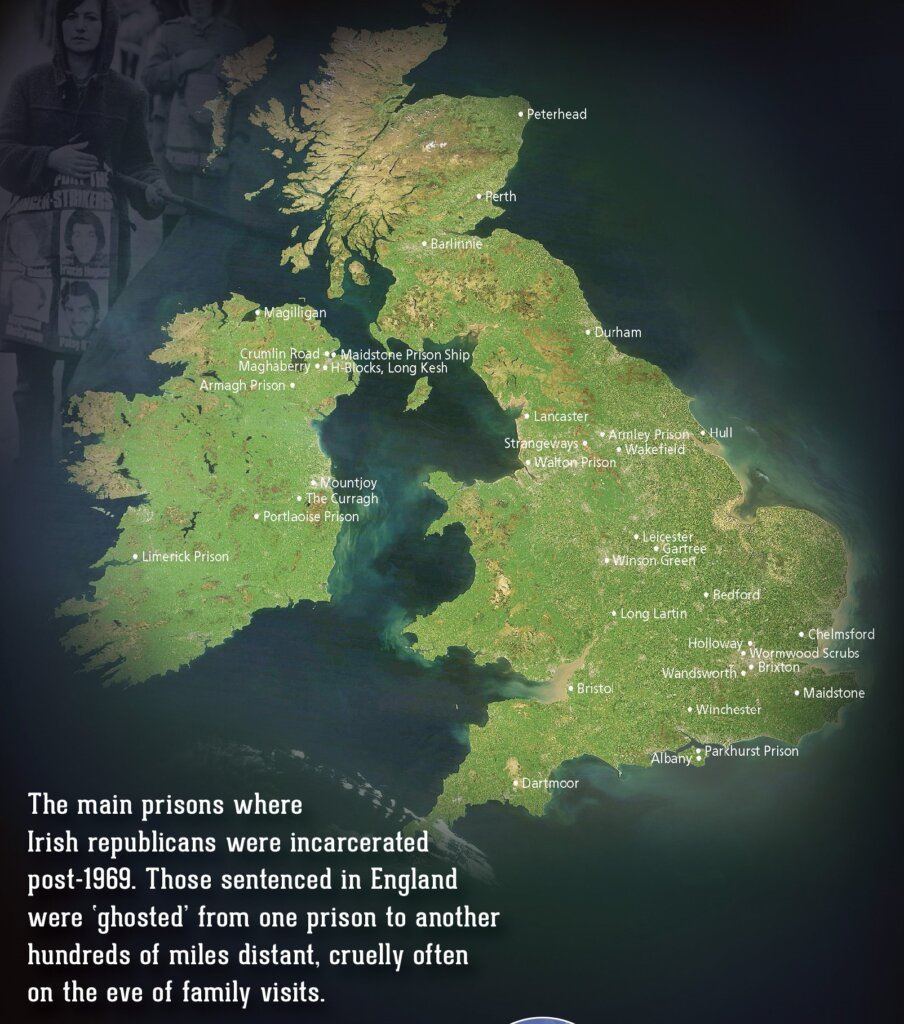

The book is black. On its back is a green map of Britain and Ireland marked only with the names of prisons that held republicans.

On its front are clasped hands representing the spirit that gave rise to its title, The Comrades, along with a list of its contributors, each of whom has written a short essay of reminiscence about one of the twelve republican hunger strikers who died since the conflict in the North broke out, starting with Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg and ending with Mickey Devine. Each of the writers was a Volunteer who did time as a POW.

Some of the hunger strikers you meet early, in their innocence, before war came to them. Paddy Quinn introduces us to Raymond McCreesh delivering milk to a local Spar shop in Belleek. Bik McFarlane informs us that Kevin Lynch captained the Derry Under-16 hurling team that won an All-Ireland. Mick Culbert quotes Ian Milne describing Francis Hughes and a friend releasing a pair of goats into the grounds of Clady School. Colm Scullion describes Thomas McElwee trying out a Cockney accent while reading John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps for Master ‘Baldy’ McKenna at Bellaghy Primary School and later trying to personify Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumblebee as he darted around the schoolyard. ‘They were very happy memories, full of mischief and innocence.

‘It was 1968 and everything was about to change forever.’

All here changed in a manner and with a totality that may only happen in times of war. All schooled themselves in history and politics, all took up arms in yet another Irish war of liberation, and all entered a network of prisons that were gulags in all but name, most of them in the cages and later the blocks of Long Kesh. Here at least they had the benefit of a command structure and comrades by the score set on breaking a prison regime that had been designed to break them – unlike Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg, who were doing their time in England. All here perceived that the attempt to criminalize them was an attempt to criminalize their people. They went naked, smeared their waste on their cell walls, endured humiliations and violent assaults and in some cases systematic torture, not for an hour or a day but year after year, and finally starved to death in order to assert who they and their communities were and how they would be defined. They placed themselves into the metallic jaws of an infinitely resourced, legally protected, cynical and sadistic regime, aided at times by the Catholic Church, as when the Bishop of Leeds ordered the prison chaplain not to say Mass in the presence of Frank Stagg, or by the Irish state, who hijacked his body and buried it in an unmarked grave. They did not flinch, or at least did not allow their flinches to be seen.

You see them thinking, strategizing, upping the ante, passing messages and tobacco, singing songs and slagging and telling stories through their cell doors, getting beaten and sometimes beating back. Thomas McElwee dropped a vicious warder nicknamed The Beol (The Lip) with a flurry of punches when The Beol tried to get his fingers in his mouth for an inspection. Jaz McCann describes Joe McDonnell stiffening his legs as wardens repeatedly tried to buckle them with kicks. He goes on to write of the aftermath of the prisoners deescalating the protest in the misplaced hope that concessions might come:

‘The Screws were cocky, the governors smug and confident that they had triumphed. So, we responded. We smashed our cells and returned to the protest. The riot squad arrived. We were trailed out, ran to another wing through a gauntlet of baton-wielding Screws and thrown into water-logged cells. There was no glass or Perspex in the windows and we had no blankets. All night we were left. It was the middle of winter, so we had to keep moving. To stop was to freeze. Next morning, we were moved to H6 where a reception committee of pumped-up Screws was waiting. We were subjected to further beatings and tossed into cells. Exhausted, battered and bruised, I lay in a heap feeling sorry for myself. The wing was deadly quiet. I suspected everyone was feeling the same.

‘Then, breaking through that heavy silence, came the voice of Joe.

‘“Lads, there’s going to be bad days for these good ones.”

‘It was a clarion call. It had the desired effect. The wing was aroused. Laughter and banter replaced the silence. As was characteristic, his humour defused the tension and breathed fire into our bellies. It sent a message out to the Screws – do your worst, it only makes us stronger.’

You meet the hunger strikers’ families. Like them they had to be strong in ways that reversed nature. They had been ordered by their children to refrain from saving their lives. Jim Gibney recalls the prison doctor detaining Bobby Sands’ mother and sister to describe how his organs would break down and that they could intervene when he went into a coma and take him off the strike. The doctor didn’t offer them a seat. Mrs. Sands asked to see her son, who asked why she had been delayed. She told him why. ‘It was extremely difficult to watch Bobby tell his mother to listen to him and no one else.’ The scenes depicted here keep rising beyond the imagination, such as when Michael Gaughan, on hunger strike and being force fed in Parkhurst prison, responded to his mother’s letter imploring him to give up the protest with this –

I want you to understand that my hunger strike won’t end until I am in a prison in my own land. It is no use advising me on the “worth” of my strike; that is something only I can decide. Why do you ask me to eat? Don’t you know I will never betray my own beliefs? Don’t you know that you ask what the British can’t achieve, with force-feeding or any other way – namely the end of my hunger strike?

‘I know that you worry. That’s the price life or God has put on you for being my mother. I know that you will have to bear it, as I have to bear being the cause of your worry. That’s the price life has put on me. I know that you can’t understand the way I conduct my life, but your not understanding my way of living does not mean that you know better than I how I should live it.’

Son loved mother, as mother loved son. When she travelled from Mayo to England to see him, she said, ‘He put his arms around me and both of us cried….Michael’s hands were ice-cold and I could smell death in the room.’

In this book death is never far away. In the prison hospital where, if they had strength, they gathered, each hunger striker can after a certain point of debilitation see the more advanced hunger striker, their growing emaciation, blindness, breakdown of the body’s material, the flickering consciousness, the families watching. Each knew the signs. Each knew nearly to the day when their comrade would die. As they knew it of themselves. They were young men. Some had children and wives and girlfriends they loved and wanted to go on loving. Victor Frankl, in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, describes the apathy that soon settled upon himself and the other inmates of Auschwitz. It was the reverse, it seems, for the prisoners in the blocks. Their consciousness, their knowledge, their appetite for life had been quickened by struggle and the camaraderie they found there. The hunger strikers had hopes to the very end, particularly after Bobby Sands and others won elections to the House of Commons and the Dáil, that the British government would accede to the validity of their demands and that they would live. Their deaths were both intimately and publicly observed. The book brings you there, one by one through the twelve.

But it also brings you life – the prisoners’ curiosity, imaginations, humour, will. Martin Hurson singing March with O’Neill off-key and delightedly persisting as the abuse rained down on him. Patsy O’Hara’s broad smile as he went off to the hospital wing, likely to die. The book is replete with such examples.

Thirty years ago I was at a talk given by Gerry Adams at a packed Quaker Hall in central London commemorating the tenth and seventy-fifth anniversaries of the deaths of Bobby Sands and James Connolly. He spoke of how people may hold in their heads images of the skeletal Bobby Sands and James Connolly strapped to his chair as he faced the firing squad, but reminded the audience that these men spent much more time living than dying and though much about commitment could be taken from the deaths more was available from the lives. Bobby Sands was among other things a rather volatile footballer who started a community newspaper, and James Connolly organized pensioners’ outings to the seaside. They were living beings, of and to an exceptional degree for their communities. He went on to say that he had attended many republican funerals at which it was said that ‘we owe it to the dead to continue’ and that while this was true it was finally to the living that the obligation lay.

Somewhere along the road to his death Frank Stagg met a prisoner orderly in for an act of violence. He was Tom Magill, aged nineteen, from a loyalist area of north Belfast. Frank Stagg told him, ‘Educate yourself, learn about your culture, be proud of who you are, don’t waste your life in here.’

‘His words challenged me and shook me to the core,’ Tom Magill wrote. “‘I listened to my enemy, I.R.A. Volunteer Frank Stagg.’

He listened so well that he founded a theatre company after his release and staged a rendition of Bobby Sands’ poem The Crime of Castlereagh.

Thomas McElwee wrote a ‘Last Wish’ shortly before his death, calling not for vengeance or that his coming sacrifice ring through the ages, but rather wishing it to be known that ‘I would rather live than die but if I have to die / I would like to let the people know that / I bear no animosity, / no ill feeling towards anybody. / I would like to live among the people / as a social worker, / and promote peace and harmony among / Catholics and Protestants. / and also with the British.’

Martin Hurson, like Gerry Adams here in his piece about Kieran Doherty, likens the hunger strike to Easter 1916, and, as Yeats wrote about that earlier event, thought that after the sacrifice nothing would ever be the same again. ‘All will change completely.’ And it has. The community the British strove to crush into submission and criminalize and that the hunger strikers strove to redeem walk differently now, with confidence, towards a future of their making. There is a direct line from marches to war to hunger strike to Sinn Fein’s entry into politics, and the ensuing peace agreement, the growth of Sinn Féin through the island and the drawing closer of a borderless, agreed (or mostly agreed) united Ireland and, perhaps, ‘the laughter of our children’ foreseen by Bobby Sands.

You do not move through a book such as this as you do through most others, collecting information, reflecting, being entertained, riding the wave of a story. It is a short book, but you know you are meeting something large and important and very real, enough so to bring lucid and life-loving young people to risk and sometimes to lose their lives in order to serve it. This existential act, for an outsider, is beyond imagining. A mystery. The Comrades and such recent books by POWs, like Patrick Magee’s Where Grieving Begins or Jaz McCann’s 6000 Days, if anything only enhance the mystery. But they also bring you closer to the source.

– Timothy O’Grady

Tim O’Grady’s book, Curious Journey—An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution, which he co-authored with the late Kenneth Griffith, will be reissued in 2022 by Greenisland Press