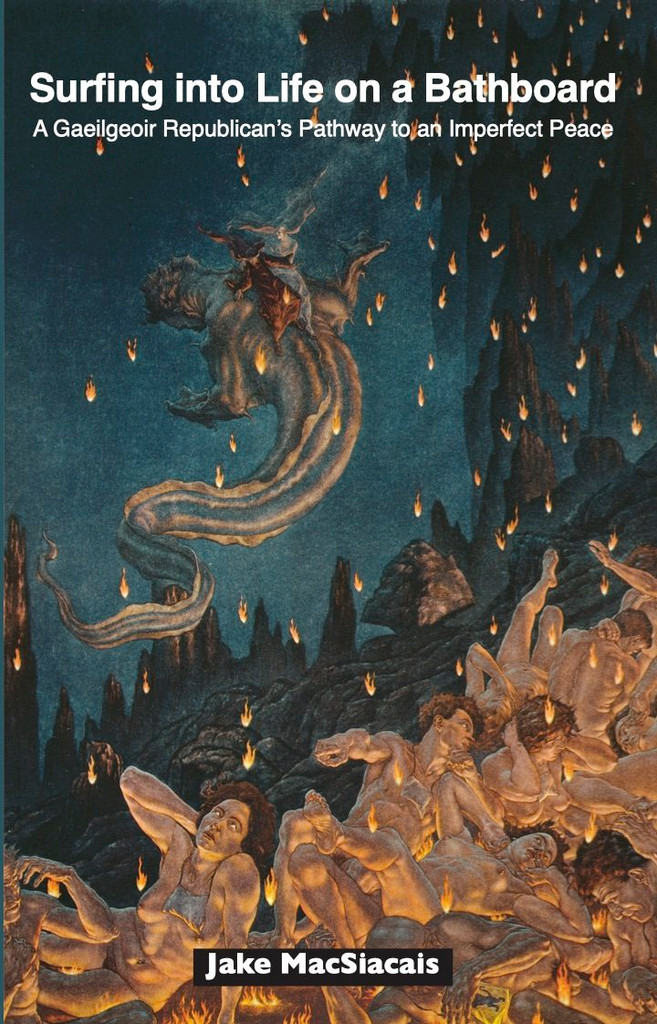

This is the enigmatic title of former blanket man Jake Mac Siacais’s memoir which previously was published as gaeilge. Here, guest reviewer Roy Greenslade gives his opinion on the book, part of the growing canon of prolific republican prison literature.

-oo0oo-

‘I LEFT the Republican Movement on Thursday October 16th 1997.’

This bald statement follows pages in which the author has prepared readers for a decision he took with the greatest of sorrow and the deepest of regrets.

It did not mean that Jake Mac Siacais, whom I knew as Jackson when our paths first crossed in the dark days of the 1980s, stopped being a republican. He resigned from Sinn Féin because he could not support the settlement which ended the war.

To reach that point, he tells us, he went through ‘mental hell’ as he struggled to come to terms with a deal that in his view ‘would lead to a false peace where the root causes of the conflict would be unaddressed and where dishonesty and pretence would be ingrained in the entire process.’

His inner turmoil was undoubtedly shared by everyone involved in the protracted negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement (GFA). It was a compromise and therefore, by its nature, open to criticism, especially by the soldiers who fought the British to a standstill.

It is not necessary to agree with Jake to appreciate the sincerity of his viewpoint. We should not denigrate a man who acted on his principles, unsettling as his viewpoint might be for those who believed they achieved the best possible outcome in the circumstances. Nor must we overlook Jake’s considerable contribution to the struggle, in and out of prison.

Indeed, the first two-thirds of this book, which cover his periods in jail, make for painful reading. This is hardly the first revelation of the harsh treatment meted out to republican prisoners, but together, all of these first-hand accounts of British/Unionist brutality amount to a hugely important historical record.

It is impossible to read about the immorality of gangs of prison warders subjecting naked men to vicious beatings, many of them teenagers, without being suffused with anger. Yet years of such torture failed to break their spirit, which is a remarkable testimony to their courage. Jake’s own strategy for survival in the H-Blocks – ‘passive resistance and silent defiance’ – earned him plenty of punishment.

There is no special pleading. He sets his own trials and tribulations within the context of his comrades’ sufferings. One of the features of these shocking jail memoirs is the stress their authors lay on the collective. ‘I’ never supplants ‘we’.

They also emphasise the importance of morale-boosting small victories. In one such anecdote, Jake tells how prisoners cleverly pressured the governor into ensuring their football was thrown back by screws when it went over the yard fence.

Every victory, however, should be balanced against instances of casual cruelty, such as the drenching of prisoners with boiling water. What inhumanity was that? Did the screws go home and boast to their wives what they did at work that day to defenceless men?

Jake makes clear that he was not entirely convinced about blind obedience to the resolve not to wear prison uniform, seeing it as a tactic, and wondering about the wisdom of the movement’s ‘tendency to elevate tactics into principles.’ This is an early hint of his later questioning of compliance with the leadership’s stance.

One of the poignant features of his account is his weaving of the personal with the political, such as coping with his mother’s death while agonising over the move towards a peace deal.

This format can be irritating because he refuses to tell his story chronologically. It also means there is some repetition. But those literary cavils are beside the point because it is his post-prison ruminations that are the core of a book, rightly regarded as ‘uncomfortable.’

Jake deals at length with the central argument about the GFA: the creation of a power-sharing government based at Stormont which, in his view, gave unionism ‘a new lease of life’ by providing its adherents with a political veto.

He considered it to be the culmination of ‘the flawed nature’ of the peace process. As such, it amounted to a violation of the IRA’s constitution and, by implication, was an insult to those who had fought and died for the republican cause. He lost faith in the leadership and rejected the pragmatism, which he believed was embedded within the process.

His parallel complaint, deeply felt, was that throughout the lengthy progress of the negotiations there was far too little internal communication.

He takes care to emphasise that he has no truck with those who wished to continue the war, the militarists. And there is much to applaud in the way he conducted himself once he decided to quit.

He did not seek to make a fuss by indulging in public criticism. He respected the opinions of those who took the opposite position. He retained his friendship with most of his former comrades.

I re-read the passages in which he made his case. They are coherent and sensible, if overly imbued with idealism. Nothing necessarily wrong with that, except that making peace with a powerful nation allied to a cohort of planted, intransigent super-Brits, was always going to result in an imperfect settlement. The GFA has to be seen, after all, as a step on the path to future perfection – a united Ireland.

But I am loath to be critical. I did not suffer the way Jake did, nor the way communities in the Six Counties have suffered ever since partition and, most particularly, throughout the thirty years from 1968.

The final passages in this absorbing book chart Jake’s years as, for want of a better phrase, an Irish language activist. They illustrate both his commitment to a Gaelic Ireland and the unionists’ determination to prevent it. During his work for Forbairt Feirste he was faced with the kinds of difficulties he predicted: unionists have succeeded, thus far, in frustrating the official adoption of the Irish language.

Then, as if prison and his disappointment over the GFA were not enough, he was beset by depression and suffered a breakdown. So, I would guess that writing this book has been truly cathartic. It may not comfort him to recall Yeats’s observation that ‘peace comes dropping slow’. But that, dear Jake, is the reality.

-oo0oo-

Surfing into Life on a Bathboard: A Gaeilgeioir Republican’s Pathway to an Imperfect Peace by Jake Mac Siacais, Beyond the Pale Books, can be purchased from An Fhuiseog (the Lark bookstore) here or at the Sinn Féin Bookshop, Dublin, here or from Culturlann, Belfast, here or from the publishers here

Roy Greenslade is a journalist, author and former Professor of Journalism, City University of London. From 1992 until 2005 he was media commentator for The Guardian.