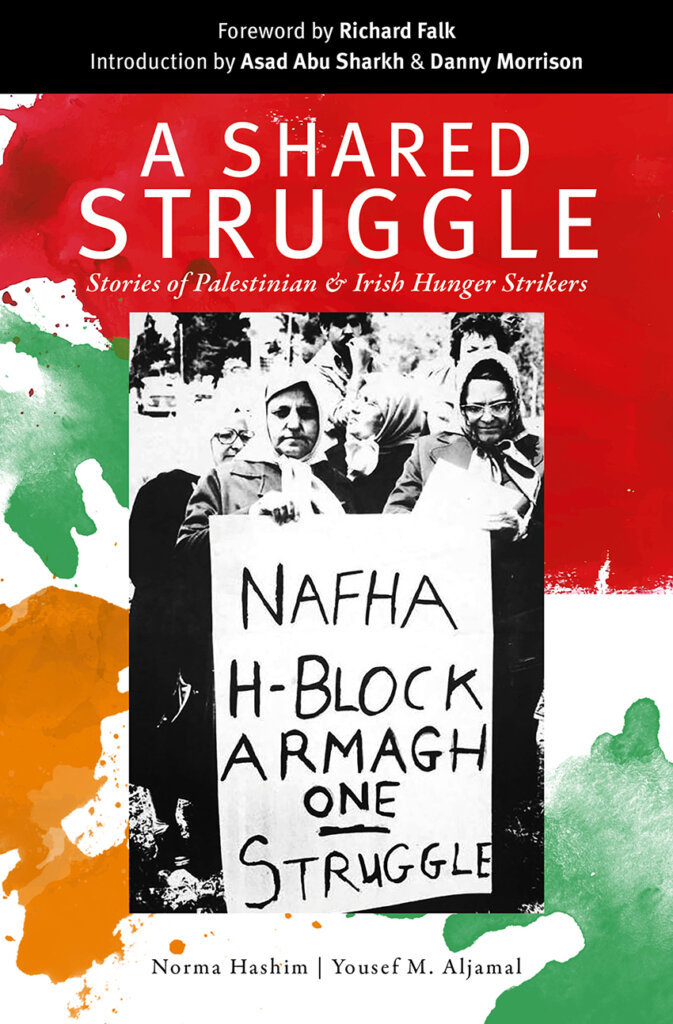

As a result of a collaboration between Palestinian and Irish republican activists a new book, the first of its kind, has been published by An Fhuiseog in West Belfast and brings together the experiences of surviving hunger strikers from both nations. The editors were Asad Abu Sharkh, International Spokesperson of the Great March of Return, and Danny Morrison, Secretary of the Bobby Sands Trust. The Palestinian contributions were translated by Yousef M. Aljamal, design by Low Seong Chai, and the overall production was supervised by Norma Hashim whose third Palestinian book this is, working alongside Yousef.

The Foreword was by Richard Falk, author and Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University.Here the book is reviewed by Belfast-based Palestinian Mohammed Samaana.*

This book is an essential historical account of heroism, steadfastness and resilience of Irish and Palestinian political prisoners in British and Israeli jails, respectively. It is unique in its style in the sense that it is not written by historians, academics or a reporter who can interfere with the narrative by the nature of the questions. Instead it is political prisoners telling their own stories and experiences of hunger strike. This gives the book credibility, authenticity and makes it a primary source and a reference book for historians, researchers, universities, human rights organisations and anyone interested in this field.

Telling it as it is gives an insight into the cruel and inhumane way these women and men were treated behind bars. This is reflected in the demands of prisoners, as they illustrated themselves, which they rightly maintained that all demands were in line with the International Law. Irish prisoners wanted to be treated as political prisoners not criminals and to wear their own clothing. They also wanted the right to receive a weekly food parcel, the right not to carry out prison work and the right of freedom of association. Irish prisoners in Britain wanted to be transferred to jail in the North where they could be closer to their families and with their comrades. Female prisoners in Armagh demanding political status protested against confiscation of black clothes which they wore to mark particular occasions and which had actually been approved by the prison censor.

Palestinian prisoners’ demands evolved and changed over the years. They refused to address the jailers as ‘Sir’. They wanted mattresses to sleep on as well as bedding and clothes suitable for the winter. They asked for pens and papers and electric fans to cool the hot cells in the summer. They also demanded an end to harassment of female political prisoners who were put in jail with Israeli criminals. Additionally, they asked to end the harassment of their families and to allow visits by families from Gaza. Ironically, they had to go on hunger strike to get the Israeli authorities to provide medical care for sick prisoners. They also wanted an end to the arbitrary transfer of prisoners between sections and jails and an end to attacks on prisoners by the Israeli guards and their dogs. Other demands included setting up phone lines to contact their families and to improve the quality of the food in the prison canteen which did not offer meat or vegetables. Female prisoners also participated in the hunger strikes.

A frequent demand by recent individual Palestinian hunger strikers is to bring their illegal administrative detention to an end. It is a form of detention similar to internment where a prisoner is put in jail without a charge or trial for a period of a few months that can be renewed indefinitely without any explanation. This form of illegal detention was implemented by the British during their cruel occupation of Palestine in the first half of the Twentieth century when Britain invaded Palestine in order to prepare it for the Zionist invasion and colonisation after partitioning parts of the Arab world with France. This illegal policy of detention has been employed enthusiastically by Israel.

Both Irish and Palestinian political prisoners made it very clear that turning their empty stomachs into a form of passive resistance—that included risking their lives in a process that a number of them actually died—was the last resort to win basic rights guaranteed by International Law. This civilised peaceful form of resistance was met by brutality by both the British and the Israelis. As a health care professional, I find it shocking that British and Israeli medical personnel were involved in the physical torture of prisoners, including force-feeding them which led to the death of some of them.

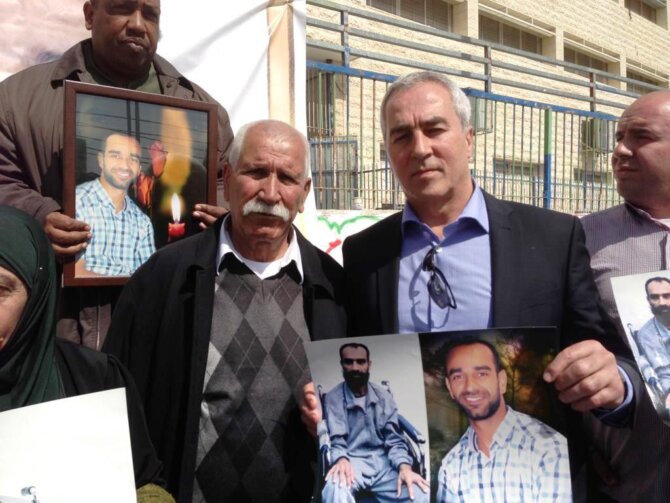

Former IRA hunger striker Pat Sheehan MLA with the family of Palestinian hunger striker Samer Tariq al-Issawa in 2013

The prisoners also spoke of how they experienced the physical and psychological impact of being on hunger strike as well as the impact on their families. The fearless prisoners stared death in the eyes but lived to tell stories of heroism, of how the British and the Israeli jailers failed to break their will either by using physical violence or by tempting them to eat by putting delicious food in front of them all day or barbecuing food nearby. Some former hunger strikers became elected representatives who negotiated peace deals and became ministers in government.

There is much reflection on the reasons behind the success or failure of a hunger strike. They identified media coverage and public support as crucial factors. Unity and the general political situation were also important. Lack of experience, disunity and biased media distortions had the opposite effect. If one hunger striker broke his strike, this would have a devastating effect on the rest of the prisoners.

The book is one of these books that I refer to as a magnet which you cannot put down until you finish it. Actually, I forgot about my own food while I was reading the stories of hunger strikers.

Some died as a result of torture. Some were blackmailed through threats to their families. But prisoners also converted jails into academies where they educated each other about history, economics, philosophy and other subjects. Some of them finished university degrees and postgraduate courses. Others wrote fiction and poetry while in jail.

Let’s hope that this book will be the start of a series documenting the experiences of prisoners and other shared stories of struggle between the Irish and the Palestinian peoples.

(Books can be ordered online from An Fhuiseog and the Sinn Féin shop in Dublin.)

*Palestinian-born Mohammed Samaana witnessed the first Intifada in 1987. After a short nursing career in Jerusalem, where he was subject to Israeli restrictions on movement, he had to leave in order to further his education. He received City & Guilds diploma in journalism in 2007 and a master’s degree in nursing from Queen’s University of Belfast in 2011. As a freelance writer he has written about the Arab-Israeli conflict and politics in the Arab world in general. He has also written on racism, immigration, Islam, gender-equality and social and political issues in Britain and Ireland. He has been published in Fortnight, Belfast Telegraph and Metro Éireann in Dublin. He also published a number of articles in Arabic in different media outlets. He currently contributes to the ‘Informed Comment’ website.