Fifty years ago today, 3 June 1974, Michael Gaughan, from Ballina, County Mayo, died on hunger strike in Parkhurst Prison.

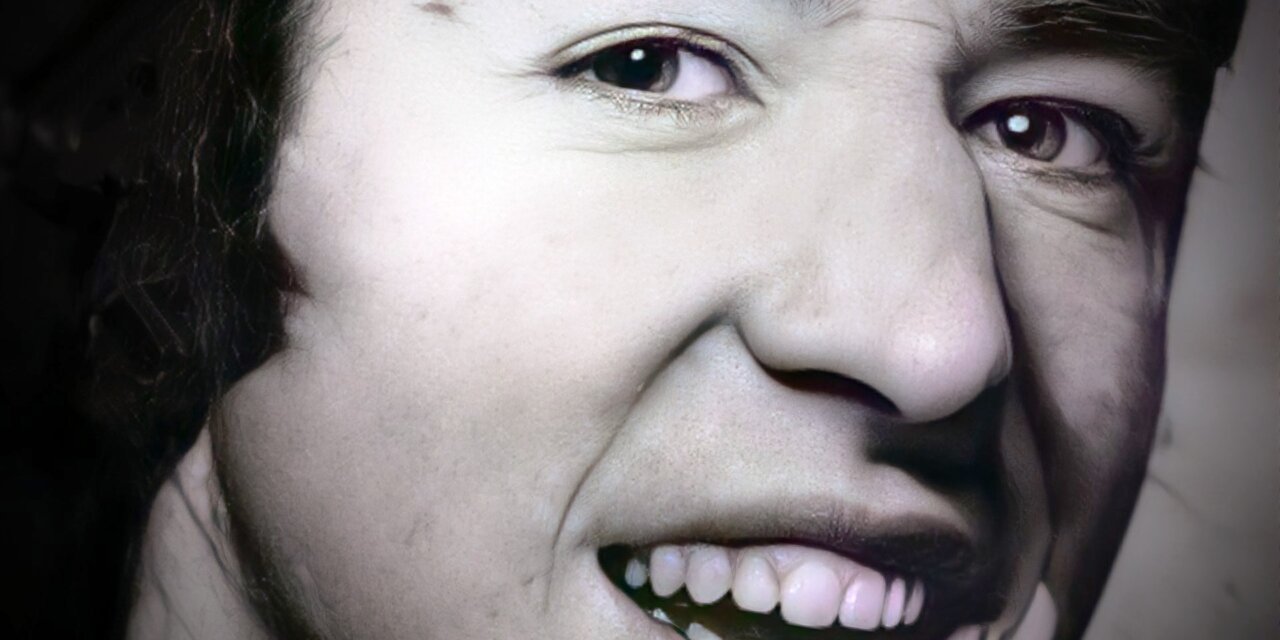

Michael was one of the earliest IRA Volunteers to be imprisoned in England in the post-1969 phase of the struggle, sentenced to seven years on 23 December 1971 for his part in a bank raid. His parents, Delia and Paddy, had no idea their son had joined the IRA. Delia said that she was astounded that the earnest young man she cherished as the quietist, gentlest of her six children had become a republican activist. His sister Tina recalled, ‘He was always talking about the North and getting the British out. He was eventually recruited into the IRA in London, but he was very protective of mother and father and he did not want them to know.’

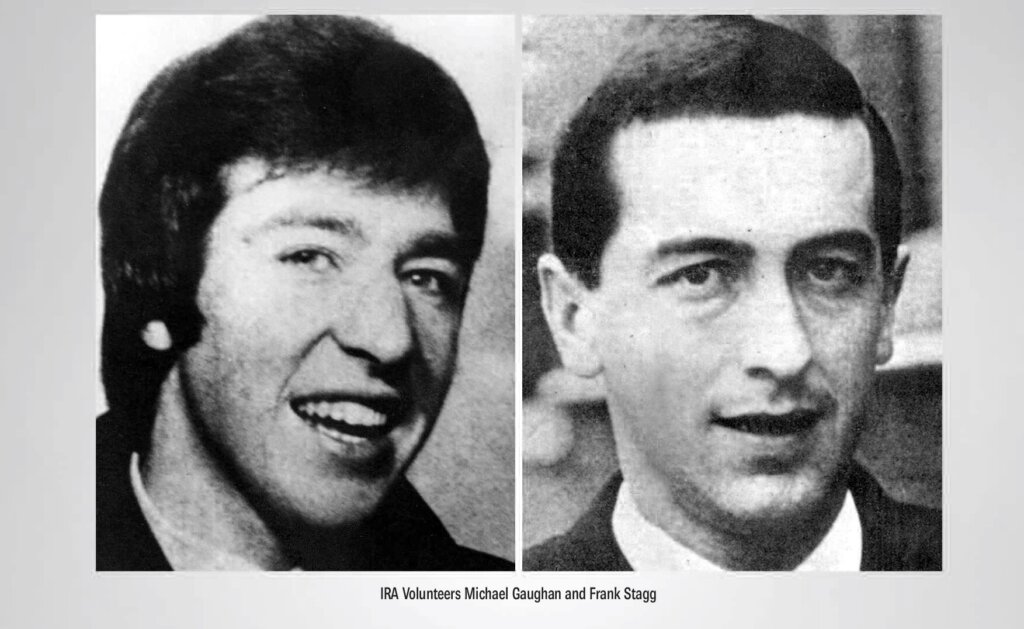

Michael and Frank Stagg were Mayo men who had left home, Michael at sixteen, because of poor economic prospects, seeking work in England. Michael joined Clann na hÉireann, a republican organisation of exiles who supported the republican cause.

He was aged twenty-one at the time of his arrest and spent the first two years of his prison sentence in Wormwood Scrubs and then was moved to the Isle of Wight’s top security prisons—first, Albany, in May 1973, and then, in 1974, to Parkhurst where he was to die. Frank Stagg, sentenced with other IRA Volunteers from Coventry, arrived in Albany in December 1973, followed by Paul Holmes in January 1974 when he came off hunger strike.

Paul had been arrested with other Belfast republicans in March 1973 and sentenced on 15 November for causing explosions in London. They included: Liam McLarnon, Martin Walsh, Gerry Kelly, Hugh Feeney, sisters Dolours and Marian Price, Martin Brady and Billy Armstrong. Eight of them went on hunger strike, including Paul for about thirty days.[1]

Michael, Paul and Frank refused to do prison work and campaigned for political status.

Four of the Belfast prisoners—Dolours and Marion Price, Gerry Kelly and Hugh Feeney, who were given life sentences—continued their hunger strike demanding repatriation to a prison closer to home in the North where prisoners had political status.

Michael and Frank joined this hunger strike on 31 March 1974, initially in solidarity with Paul Holmes on a temporary fast when he was punished with a bread and water diet for refusing to obey orders, but they escalated their protest to a full strike, demanding the right to wear their own clothes, not to do prison work and to be repatriated to a prison in the North.

10 April 1974, Michael and Frank are moved from Albany Prison’s punishment block to the hospital wing of nearby Parkhurst Prison.

22 April 1974, the men are force-fed for the first time. Michael is forcibly fed for eight days

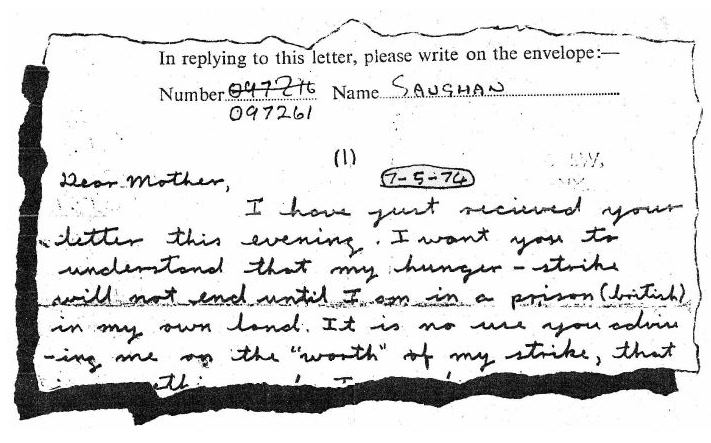

Delia Gaughan had written to her son begging him to give up the protest.

7 May 1974, Michael to his mother

‘I want you to understand that my hunger strike will not end until I’m in a prison in my own land. It is no use you advising me on the ‘worth’ of my strike that is something only I can decide. Why do you ask me to eat? Don’t you know that I will never betray my own beliefs? Don’t you know that you ask what the British can’t achieve, with force-feeding, or any other way—namely the end of my hunger strike?

‘I know that you worry, that is the price life, or God has put on you for being my mother. I know also that you will have to bear it, as I have to bear being the cause of your worry, that’s the price life has put on me. I know that you can’t understand the way I conduct my life, but your not understanding my way of living my life does not mean that you know better how I should live it.

‘I know that you worry, that is the price life, or God has put on you for being my mother. I know also that you will have to bear it, as I have to bear being the cause of your worry, that’s the price life has put on me. I know that you can’t understand the way I conduct my life, but your not understanding my way of living my life does not mean that you know better how I should live it.

‘I ask now that you stop your calls on me to end my hunger strike and instead give me your support in what ways you can. Don’t join the British by trying to end my strike. I know Ma that your reasons are very different in wanting it to end. The British hold my life and health in their hands, they may take both rather than give way to my just demand, but I will stand by what is just all the way. I ask you to bear your worry and stand by me. When anyone asks you anything about me, say you stand by me in whatever I do and I know my own mind, and then say no more.

‘I don’t want these words to sound hard, but only to help you understand I am what I am and there are no two ways in this. I have never been much of a one for ever showing my feelings about you all, I won’t start now either, but don’t think that I don’t care deeply about all our family, I do.

‘Well, enough of that now, I can tell you that I enjoyed my visits with John and Des. It was good of Des to give up his time and money to come with John. No matter what, he’s a good friend. John was looking smart and I thought fit and not a bad weight at all. I am sure they have done the couple of things I wanted as soon as they got back. They tell me Dad is keeping well, but that’s nothing new, the man is a horse! I’m glad to hear you are all in fair shape.

‘Things are going well in regard to the strike here as we got the whole front page in a ‘well known’ republican paper in last week’s issue which covers the whole of Ireland. All the lads in Ballina will have good reading and people do care so cheer up!

‘Somehow, someway we shall overcome. Just you wait and see.

‘Well I will finish off here for now as I can always drop you a few lines in a few days’ time again. I’m off the smoking and I can afford to buy some extra stamps, for a while anyway. Just heard on the news that there was a demo in London against force feeding by a group of English doctors – good on them!’

9 May 1974, and for the following four days he is again forcibly fed

21 May 1974, Michael to his mother

‘A few lines to thank you for your letter which I received all right. I was very glad to see you found my last letter a help in understanding my reasons for the hunger strike. Like yourself I can only hope we have results soon. Glad to hear you are all keeping well. You should spend a good long holiday at Gran’s. It will do you good. Noel’s week away with lads of his own age is a good idea too. Send me a biro as this one is running out and the canteen are out of stock.

‘Yes, you can send me some money if you want to. Just wait until I am in the North and I’m after you for food parcels!

‘I asked the lads to send the Western People but no sign yet. Any reply about those letters yet? Let me know if you can.

‘Frank’s people (Stagg family) are coming to see him this weekend, so I’m sure they’ll call to let you know how we are. Well Mother I will finish off here for now and I’ll write again soon.’

24 May 1974 and subsequent days, Michael is forcibly fed on another five occasions

29 May 1974, Michael to his mother and father

‘This is just a few lines to thank you for your letter and money and as you can see, the biro. I’m having second thoughts about letting you come to see me, perhaps with dad or John. The only thing I ask is that none of you try to ask me to give up my hunger strike. I would not like to have to refuse to do anything for any of you, but my code of life by which I live would make me refuse anyone’s attempts to give up what I believe in.

‘I have not put this very well but I hope you understand what I mean. I don’t know if they will let you into the prison mother as you are not on my visiting list, but you can ask the prison on the phone. I am of course thin now and frailer than when you last saw me. Maybe it would be better if dad just came himself. It was really great to read in your letter that you made some calls to friends in London. Those people are doing their best to get us moved. They are just plain people who want to help. Mrs Phillips should be able to give you a fair amount of help as to the people who are helping us. I had Mass in my cell last Sunday and one Sunday a priest said Mass for all our family.

‘Anyway Ma, see what you want to do about the visits, I think it would be better if it were dad who just called as I don’t like the thought of you coming to a place like this. It’s OK for a man but I don’t want to see you getting upset, especially when nothing can change.’

30 May 1974, Michael’s mother visits him, knowing that he is dying

‘When I went into the room, I was looking for Michael, but the only person there was this figure with a warder at either side. He looked like someone from a concentration camp. I did not recognise him. He put his arms around me and both of us cried. He said, “I knew it would be emotional.” We sat and held hands and although the warders moved away a little, they were able to hear everything. Michael’s hands were ice-cold and I could smell death in the room.

‘He asked about the family and then showed me his throat where it was sore from the force-feeding. It was red and raw and he had teeth missing. Michael began to talk about the doctor but the warder told him he was not allowed to do this.’

The warders then ended the visit.

‘Michael stood up, he could hardly stand. Both of us were crying. The warders put their hands under his arms and they kind of dragged him off.’

Describing his brother’s condition towards the end John Gaughan said, ‘His hands were ice cold and he had the look of death about him. His throat had been badly cut by forcible feeding and his teeth loosened. His eyes were sunken, his cheeks hollow and his mouth was gaping open. He weighed about five stone.’

Michael died three days later, at 7.20 pm, 3 June, after sixty five days.

On the day he died Michael prepared a statement which read:

‘I die proudly for my country and in the hope that my death will be sufficient to obtain the demands of my comrades. Let there be no bitterness on my behalf but a determination by all to achieve the New Ireland for which I gladly die. My loyalty and confidence is to the IRA and let those of you who are left carry on the work and finish the fight.’

When news of his death broke in the prison, over ninety inmates staged a sit-down demonstration in the exercise yard, remaining without food and water for twenty hours before returning to their cells. Such was the esteem in which they held Michael the prisoners pooled their meagre wages and sent the money to Delia Gaughan who got Masses said for them.

Mrs Gaughan called for an independent pathologist to be allowed to be present at her son’s autopsy. Her demand was backed by a group of fifty doctors who had demonstrated outside the British Medical Association against force feeding.

The four Belfast hunger strikers were promised they would be repatriated and they ended their hunger strike on 7 June having been force-fed over two hundred times.

Frank Stagg received a similar undertaking and ended his hunger strike on 15 June.

In July the British Government announced it would no longer force-feed protesting prisoners.

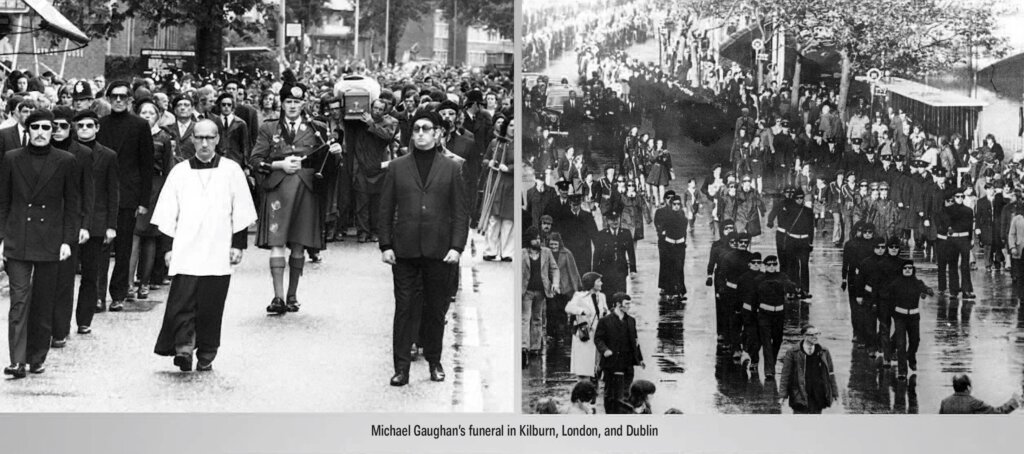

Thousands of people lined the route of Michael’s funeral through Kilburn and, again, through towns in Ireland as his cortege made its way to Leigue Cemetery in Ballina. In Ballina a group of IRA veterans, including those who had taken part in the Tan and Civil Wars formed a guard of honour.

Michael’s coffin was draped in the same Tricolour that was used for hunger striker Terence MacSwiney’s funeral fifty four years earlier.

TRIBUTE TO MICHAEL GAUGHAN

by his comrade, Danny ‘Jack’ McElduff

I’d put practically nine years into becoming a priest when the Dean of Discipline told me I’d have to get a dispensation because I’d two brothers in prison. I’d a brother Joe who was interned in the Curragh and another James was interned in Crumlin Road. That was in the 1950s.

‘But they are not criminals and internment is an unjust law’, I said to him. ‘Well it’s a very grey area,’ said the Dean, ‘and we’re safer getting a dispensation for you.’

So I left the seminary. That was a long period of time lost to me. I was twenty-three then and I went to work in England on the buildings in Colchester in East Anglia, about seventy miles from London.

Then when the Civil Rights Movement started up in the North in 1969 I returned home to see what was happening. Sometime after that I was approached by Seán Mac Stíofáin, who was IRA Chief of Staff in 1970, to go back to England. I went back. I was thirty-one then. Brendan Magill had been the OC of England but then he and Jim Monaghan got arrested and Mac Stiofáin asked me to take over as OC. I didn’t really want to do it but I agreed and I recruited a few new Volunteers.

And that’s where Michael Gaughan came in.

He came from Manchester to see me about getting involved. Michael was a Mayo man and if you know anything about Mayo people you’ll know they are very loyal and staunch when it comes to their republicanism. Michael was a cheerful, laughing man but a very serious-minded republican who wanted to go the full hog at things. The first thing that was needed in order to operate in England was money. We did a job in Manchester to get money and I then gave them another one to do—a payroll—and it wasn’t a success so rather than accept defeat the boys decided to do a bank job and of course the preparation wasn’t as thorough as it would normally be.

I was back in Colchester at that time and they brought the money to me and went to go back to London but they were scooped up on the train and I was lifted the next morning. My house was surrounded by Special Branch.

So four of us, including Michael and I, landed in Brixton. That was in 1971. Then we went on trial. I got three years for ‘receiving stolen money’ and Michael and one of the other two got seven years for robbery and the other got a year for arms offence.

We were sentenced the day before Christmas Eve and we were being taken by van through London for the court hearing. We could see all the people going about with their Christmas shopping and Michael, who had only a middling voice, bursts into the song, Twenty One Years. For the uninitiated or those too young to remember, the song described the most likely prospects for a republican Volunteer upon arrest—twenty years-to-life in jail!

Michael was very calm about the arrest and sentence. He always knew imprisonment was part of the risk. I’ll never forget the first night we landed in Brixton. In the block opposite the one we were in there was a boy with the best Mayo accent I ever heard and he kept shouting all night. I was tired and sick and wanted to sleep so I got up to the window and shouted over to him to shut up. He heard the northern accent, my country accent, and you know how news gets round a jail very quick. He shouts, ‘I knew the IRA were in the prison tonight! It’ll be a long time before you clean your arse with grass again!’

We all laughed. After Brixton we were moved to Wormwood Scrubs and then to Albany.

I remember there were Jamaican prisoners who were getting assaulted by some of the other prisoners and Michael said we’d have to side with the Jamaicans no matter what happened to us. So I went to one of the Kray brothers [notorious East End gangsters] who happened to hold the IRA in esteem and told him the story. Kray listened and finally responded, and ordered, ‘All that “cutting” of the Jamaicans will have to stop.’ That was lucky for us because there were so few of us and Kray had a lot of men with him.

Michael refused to sew overalls for the British Ministry for Defence and was given solitary. Michael was still in solitary when I was released some weeks later. He was eventually transferred to Parkhurst which was a short distance away but a much tougher regime.

Michael was the sort of person who would see a thing through to the bitter end, even if the force feeding hadn’t killed him he’d have stayed on the fast to the end. Even while in jail he always wanted to get the news from home and I remember him asking for a copy of the Western People, he wanted to get the football results.

As a Volunteer Michael was a one-off even though he’d no background in the Republican Movement. His father had been in the British Air Force but Michael just had it in him—an Irish thing—the desire to free Ireland. Michael would have been brilliant operating in rural Ireland. As republicans we’ve been brought up with big names, leadership figures, but there’s a saying, ‘Watch the little man on the side of a hill with a gun in his hand—that’s the revolutionary.’ Michael wasn’t highly educated but he was very clever. He was very political—a revolutionary.

When I was being released after the three-year sentence, Michael told me there’d better be a place for him in the IRA when he’d get out. I was well gone by the time Michael was on hunger strike. The emphasis was on the Price sisters at the time because they had been on hunger strike much longer so there was great concern about them and when Michael died so quickly from the force-feeding it was a huge shock. I was shocked because even though I knew he was on hunger strike we never thought of him dying so early on. There was no time to get my head around it. When I heard it on the news I nearly dropped.

I went to Dublin for the funeral, which was routed to go through Roscommon so we drove ahead of the cortege and onto Mayo. It was very touching, very moving. Once you got out into the country—especially from Roscommon on—there were people waiting in the towns and nearly every boreen you passed there were people waiting at the end of it. It was amazing.

Michael and his likes are a terrible loss to this country. You’re not going to get people as selfless as Michael Gaughan, Frank Stagg and the ten H-Block hungers strikers.

Some of the material on Michael Gaughan has appeared previously in a number of different publications. We would like to credit Ella O’Dwyer (former POW), Mark Dawson, historian Ruán O’Donnell, the late Shane Mac Thomáis, Seán Mac Brádaigh, Míchéal Mac Donncha, Pat McGlynn and Aengus Ó Snodaigh.