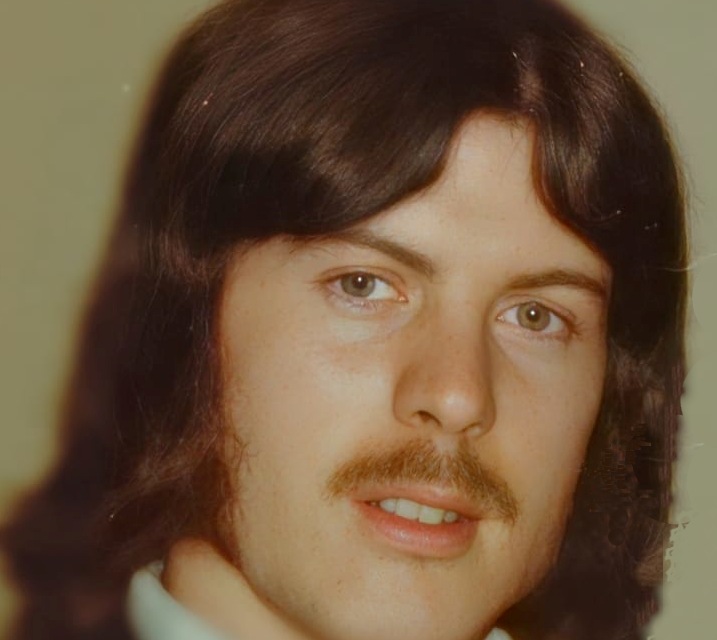

Forty years ago today Kieran Doherty became the eighth blanket man to die on the seven-months’ long 1981 hunger strike. Kieran, from Andersonstown in West Belfast, was twenty-five-years old and had been on hunger strike for seventy-three days.

After the introduction of internment in August 1971 Kieran, like many young people, had had enough of state repression and decided to join the struggle to end British rule in Ireland. He joined Na Fianna Éireann and soon came to the attention of the British Army. In February 1973, he was arrested, interrogated in Castlereagh Barracks and then interned in Long Kesh, where he spent over two years. Upon release he reported back to the IRA and was part of a very active unit in the Andersonstown area throughout 1976. He was hit hard when his friend and comrade Seán McDermott was shot dead and Mairéad Farrell (killed in Gibraltar in1988) was captured during an operation in which Kieran was also involved.

Some months later Kieran was captured on a bombing mission with comrades John Pickering, Liam White, Chris Moran and Terry Kirby.

In January 1978 he was sentenced to eighteen years and joined the blanket protest. Kieran spent all but two weeks of three years and eight months in H4 before being moved to the prison hospital during his hunger strike. He was elected TD for the Cavan/Monaghan constituency in the June general election with 9,121 first-preference votes. He died on 2 August. The Irish Government ignored the convention following the death of a TD and refused to fly the Tricolour at half-mast over Leinster House (which it later did after the deaths of Princess Diana and the British Queen Mother).

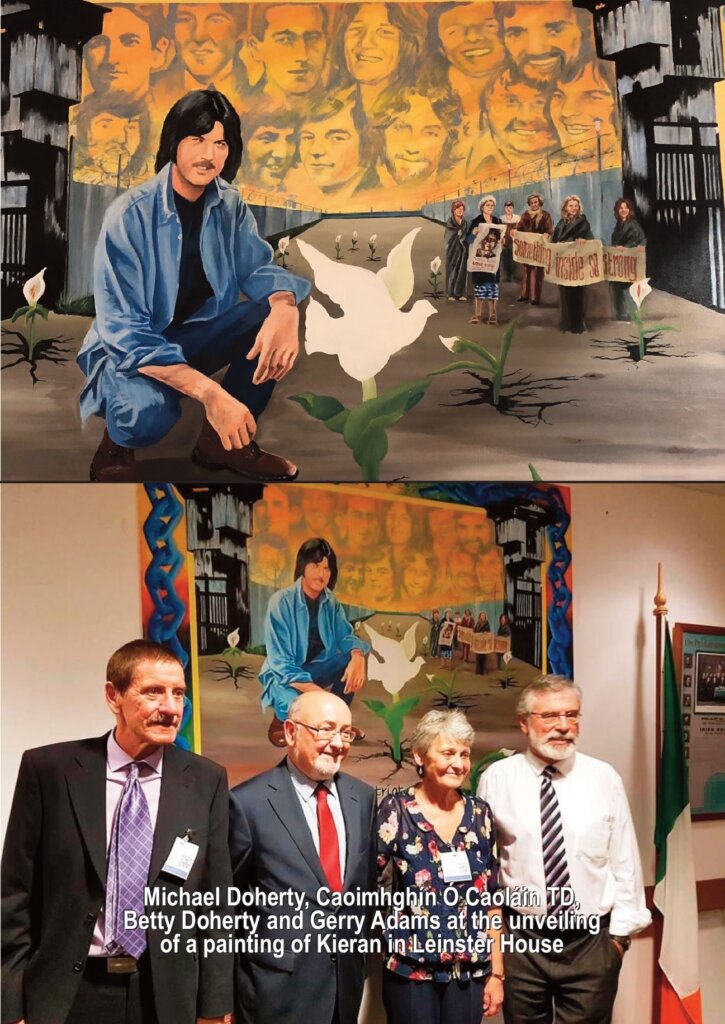

In 2016, a portrait of Kieran Doherty was put on permanent display at the Dáil, unveiled in Sinn Féin’s conference room.

In a powerful interview this week with Joe Austin, Kieran’s brothers, Michael and Terry, speak about their brother.

Former blanket man and hunger striker John Pickering in this broadcast, part of the series Guthanna ’81/Voices of ’81, talks about his friend and comrade Kieran Doherty

In a forthcoming book, The Comrades, Gerry Adams has contributed a chapter on Kieran whom he first met, along with the late Bobby Storey, when both were interned in Long Kesh.

‘Kieran and Bob stood out. Not just because of their youth. That wasn’t unusual. Alex Murphy in our cage was a schoolboy. But he was small. Kieran, like Bob, was very tall. Too long for their bunk beds. And full of vim and craic and very much part of the prison struggle of that time. Little wonder they, like others from that era, went on to play such key roles later…

‘The last time I saw Big Doc was on 29 July, 1981. His father and his brother Michael were there that day. I was visiting the hunger strikers along with Owen Carron and Seamus Ruddy of the IRSP. By this time Bobby, Francie, Raymond, Patsy, Joe and Martin had died.

‘We met Thomas McElwee, Laurence McKeown, Matt Devlin, Pat McGeown, Paddy Quinn, Mickey Devine and Bik McFarlane in the prison hospital. Big Doc was unable to leave his prison bed. Kevin Lynch was also too ill to see us…

‘Doc was propped up on one elbow on his prison bed: his eyes, unseeing, scanned the cell as he heard us entering.

‘I sat on the side of the bed. Doc, whom I hadn’t seen in years, looked massive in his gauntness, as his eyes, fierce in their quiet defiance, scanned my face.

‘I spoke to him quietly and slowly, somewhat awed by the man’s dignity and resolve.

‘“You know the score yourself,” he said. “I’ve a week in me yet.”

‘He paused momentarily and reflected: “We haven’t got our five demands and that’s the only way I’m coming off. Too much suffered for too long, too many good men dead. Thatcher can’t break us. Lean ar aghaidh! I’m not a criminal. For too long our people have been broken. The Free Staters, the church, the SDLP. We won’t be broken. We’ll get our five demands. If I’m dead, well, the others will have them.

‘“I don’t want to die, but that’s up to the Brits. They think they can break us. Well, they can’t. Tiocfaidh ár lá.”

‘I never saw Thomas McElwee, Mickey Devine, Kevin Lynch or Big Doc alive again.

‘At 7.15 pm on the evening of Sunday, 2 August, Big Doc died.’

‘I am very proud of him. I am very proud to have known him. And I am proud of all of those who voted for him and who worked for him in that summer of 1981… Forty years later we continue to be uplifted and inspired by the words and deeds of the hunger strikers.’

Yesterday (1 August) a small commemoration in Andersonstown was held at a monument to Kieran, opposite the home where he grew up in Commedagh Drive. Local MLA Órlaithí Flynn (whose father was imprisoned with Kieran) was the main speaker and said:

For me Kieran Doherty and the hunger strikers of 1981 are not just names from history books or faces that look down on us from murals, their spirit is with us every day and we continue to be guided by them in all that we do. They epitomise the ultimate resistance to British oppression here in Ireland.

Each of these men could have chosen another way, taken an easier path but they didn’t. They chose to stand up for their community, for the country they loved.

I have heard it said that the 1981 hunger strike is this generation’s 1916.

I think it certainly is in terms of Kieran’s sacrifice and that of the other 9 hunger strikers. I think it certainly is in terms of the heartache that their families went through as they stood by them to the end of their lives.

As we remember Kieran, we must always remember his family, remember the support they gave and the unimaginable pain they endured during this very difficult period in their lives.

The loyalty of the hunger strikers to the freedom of Ireland and to their imprisoned comrades in the H-Blocks and Armagh Women’s Prison was incredible.

The loyalty of their families to them was also incredible.

And Kieran’s family knew him, as only a family can know their son or their brother.

They knew Kieran as an ordinary person, just like us, with all the hopes and dreams we have as we go through our lives.

Others will have known Kieran as an IRA volunteer, they will have known him through the horror of the H-Blocks…

For the younger generation, listening to the experiences from inside and outside of the gaols at that time, we were fortunate enough to be born into an entirely different political dispensation. Although my generation of young republicans, are separated from the heroic men of 1981, only by time.

The hunger strike of 1981 and the protest by the political prisoners in Armagh and the H-Blocks brought huge changes to the struggle.

The battle for political status was not just about the recognition of the prisoners as political prisoners.

It was also about the recognition of the struggle for freedom as a political struggle not the criminal venture of propaganda and as portrayed so easily, particularly by Thatcher.

A struggle for national self-determination after 60 years of the northern statelet, an artificial border imposed on our country at the point of a gun, and a system of discrimination which was the envy of Apartheid South Africa.

It is a struggle against the imposition of mis-rule, and occupation. It was as legitimate in the H Blocks of Long Kesh as it was in the GPO on O’Connell Street.

And the people responded.

Nationally and internationally Britain’s real role in Ireland was exposed and the struggle for national self determination was vindicated by these young, brave men who were not prepared to accept the criminalisation of their struggle.

From the streets of New York to Paris to Tehran, the right to Irish self-determination was proclaimed as legitimate and Britain’s role in our country and in the brutalisation of Irish men and women in prisons was seen for what it was – that it was the criminal party.

The election of Bobby Sands as MP and Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew as TDs encouraged Sinn Fein to embark on the electoral path.

And today we can see the benefits of Bobby, Kieran and Paddy’s election.

It can be seen in the recent election results where for the first time in almost one hundred years’ unionist majority rule has ended.

These are fundamental changes on the road to a new and independent Ireland and changes which could never have came about without the sacrifice of people like Kieran Doherty.