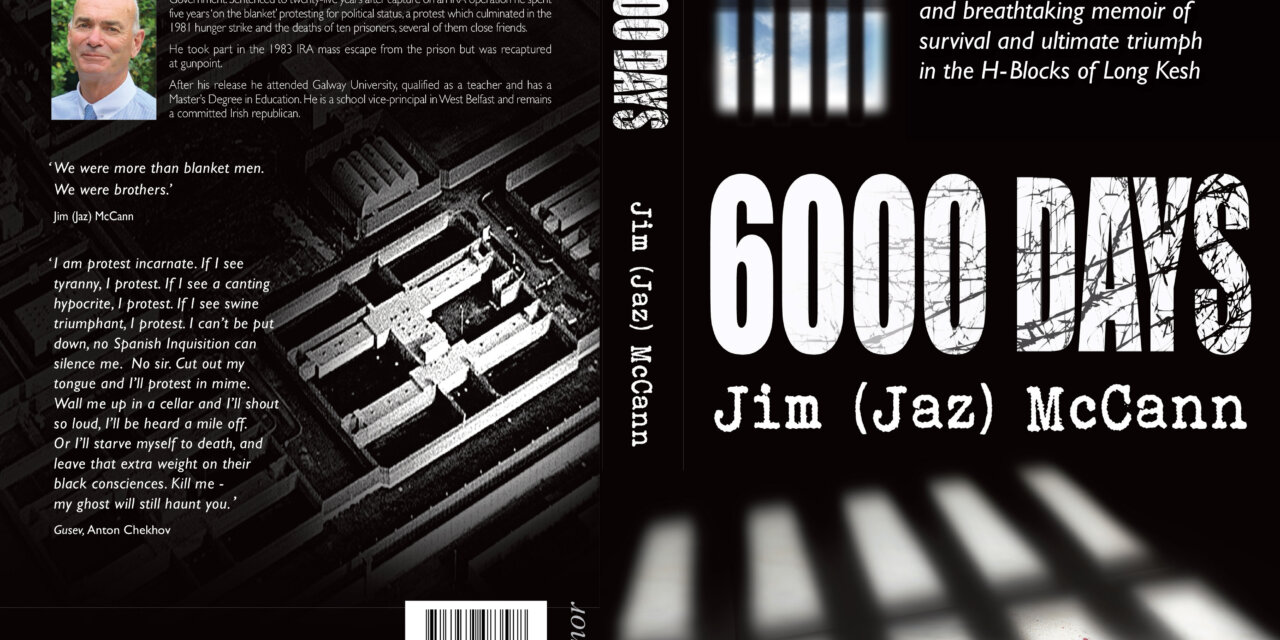

There has been huge interest in Jim ‘Jaz’ McCann’s prison memoir, 6000 Days, which has had to be reprinted to cater for the phenomenal demand. McCann served time on the blanket and knew several of the 1981 hunger strikers about whom he writes intimately and passionately. His descriptions of his comradeship and his parting with Joe McDonnell are heart-breaking.

The book can be got through An Fhuiseog (Belfast) – Facebook, An Fhuiseog/The Lark (028 90243371; Sinn Féin Bookshop (Dublin) – sales@sinnfeinbookshop.com (00353 872301882); and Blackstaff Press – https://blackstaffpress.com/6000-days-9783939483588

Amongst those who have reviewed the book are veteran journalist and former Professor of Journalism at City University, London, Roy Greenslade; former President of Sinn Féin, Gerry Adams; John Manley, Irish News; the Sunday World; and former lecturer and journalist Sean Napier on Eamonn Mallie’s website. Here is what they said:

-oo0oo-

ROY GREENSLADE*

In the concluding part of this book, Jim McCann celebrates the birth of his first child by writing: “I had overcome imprisonment… not only was I going to share it with my loved ones. It was fulfilment, it was ecstasy.”

After the previous 250 pages, in which he recorded his trials and tribulations as a prisoner in the H-blocks, we, the readers, are with him. We can understand his euphoria. We not only admire the fact that he survived 6,424 days in jail but that he managed to do so in such appalling conditions.

But it is the next sentence that makes this prison memoir so exceptional. “There had been special moments like Bobby [Sands]’s election, the escape, that first Christmas parole, but this capped them all.” This linking of his intimate domestic concerns and the wider struggle encapsulates McCann’s overall theme: republicanism unites the personal and the political.

Aged 20, McCann was sentenced to 25 years by a Diplock Court (no jury, one judge) for attempting to kill an RUC officer. He would go on to serve 17 years. At every stage of his imprisonment, through the blanket protest, the dirty protest and all the resulting brutal beatings and casual punishments, he was sustained by the fact that his refusal to bend had a political purpose.

That he did so while fearing the inevitable violence that would be meted out to him made his stand all the more courageous. Not that the modest, phlegmatic McCann even hints at his defiance in terms of his own bravery. Instead, he reserves such praise for Sands and his nine comrades who died while on hunger strike, especially Joe McDonnell. It was a uniquely sobering moment for McCann.

He writes: “Bobby’s death, and Joe following him on the stailc [strike] was a turning point in my life. I had been convinced that justice always prevails and those that fight for what is right always win through… Now reality was hitting me… being right did not necessarily equate with gaining justice.”

His admiration for the “fearless” McDonnell’s “heroic qualities” shine through his account of the routine brutality suffered by all those who refused to wear prison uniform. McCann quotes a screw who thought McDonnell “the toughest prisoner he had ever come across” and tells of his friend’s way of lifting morale after savage beatings by prison officers. He would rally his bloodied and bruised comrades by telling them: “There’s going to be bad days for these good ones.”

McDonnell, known for his banter and dark humour, was the fifth hunger striker to die. McCann calls it a privilege to have shared jail time with “this giant of a man”, commending “his selflessness and dedication to a cause he would never allow to be criminalised.”

Although the passages on the hunger strikes are, unsurprisingly, the most difficult to read, there is a virtue in the way McCann describes them. His straightforward prose, factual and devoid of adjectives, adds to the poignancy of those tragic events.

Some of McCann’s memories appeared in a previous book, Nor Meekly Serve My Time, but this fuller, detailed version offers a much deeper understanding of what it was like to spend year after year undergoing a succession of attempts by officials to humiliate prisoners in order to break their resolve.

Optimism breeds moments when everything looks as if it will turn out well. In the summer of 1978, for instance, the men “were on a high” in the belief that the prison administration was “on the back foot” and “it would only be a matter of time before political status was conceded.”

With hopes dashed, the men rely instead on raising their spirits by securing small victories against the prison regime. They smuggle tobacco; they maintain communications with the IRA leadership; they even get hold of a radio. One particular victory had wider ramifications: the election success of Bobby Sands. As McCann acknowledges, although it wasn’t clear at the time, it was to set the republican movement on a path towards a new strategy.

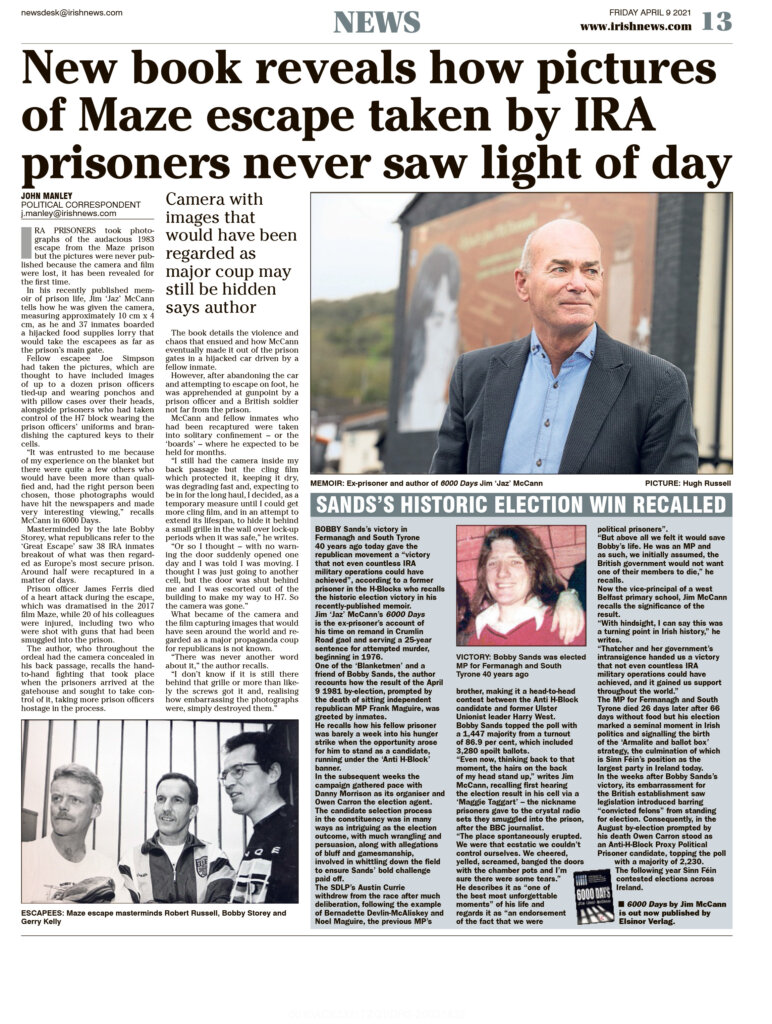

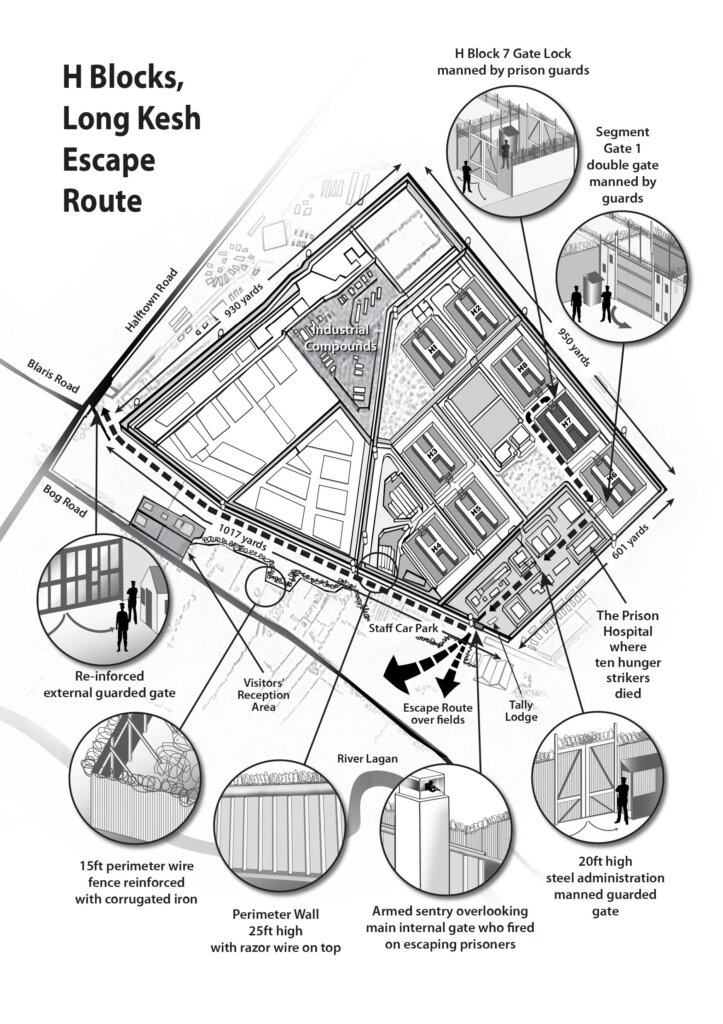

That was to prove, as we know, a slow process. Inside the Maze, in the aftermath of the hunger strike, there was a determination to take the initiative, to land a propaganda coup against the authorities. The result was the 1983 mass escape from a prison regarded as escape-proof.

Once again, it is the very down-to-earth nature of McCann’s account of his part in the chaotic enterprise that is so compelling. He conveys the tension by highlighting his personal dilemma. Should he have left the trolley in the canteen as instructed? Did he misunderstand those instructions? Was he going to be responsible for the failure of the escape?

With that drama behind him – and, no, he did not misunderstand – comes the main event: the attempt to squeeze a car between closing gates. Then he makes his break on foot, running past watchtowers manned by soldiers uncertain whether to shoot at the fleeing prisoners. McCann’s freedom was short-lived because he was quickly recaptured, but the exhilaration at having taken part helped him survive the beating by guards on his return. “The screws were like a pack of wild dogs,” he recalls.

He never lingers for long on descriptions of these terrible moments, preferring to point to the camaraderie among his fellow inmates and also to remember instances of wit. With married men being allowed to take visits, one man argued that because he was engaged, and therefore “nearly married”, he should have a similar deal. McCann’s friend, JT, replied he should “nearly take a visit.”

But it is wisdom, rather than wit, that informs the central message of this book: the power of the state can be defeated by people who put principled politics above personal gain. The sacrifice of the hunger strikers, concludes McCann, had not been in vain.

As for McCann, he graduated with an Open University degree while in jail. After his release, he went to Galway University, gained a master’s degree in education, qualified as teacher and is now vice-principal of a West Belfast school. And, yes, he remains a republican. His is a truly noble story.

*From Belfast Media –

-oo0oo-

GERRY ADAMS

Jaz McCann writes very well. The reader is quickly drawn into his world. From the opening sentences of his Prologue Jaz paints the sights and sounds, the emotions, shocks, excitement, sadness, smells and the savage brutality and amazing horrors of his 6000 days of incarceration, mostly in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh. He also makes us witness to the incredible courage, vision, commitment, solidarity, idealism, generosity, quirkiness, anger, native contrariness, humour, comradeship and stubbornness of the political prisoners.

6000 Days is an important and significant contribution to the history of the Irish penal experience, in line with Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa’s classic Irish Rebels in English Prisons and other historical penal narratives. I have long had a view that we republicans need to write our own histories. Others should do likewise. Including from a Unionist or even in this case a Prison Officer’s point of view. By setting all these narratives together the weave of our collective history – as lived in cities or rural Ireland by women, workers, the poor, by combatants, victims and in this case by our political prisoners becomes a shared history.

Embracing this and learning of the experience of others may not remove our disagreements with them but it will help us to understand and hopefully learn to live with a greater tolerance for difference and maybe an appreciation of how much we have in common. Pat Magee, another former republican combatant, has bravely tackled some of this in his memoir Where Grieving Begins.

But this important factor aside there is still in its own right an onus on us to tell our own story. Otherwise some will try to write it for us. Jaz McCann has taken up this challenge. In his understated but graphically honest way he has shared his story with us. We should be grateful to him. I defy anyone who portrayed the blanket men or the Armagh women as criminals to read it without being moved by what happened in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh in the five years leading to the summer of 1981 and the second hunger strike.

The past of course is never passed. Yes it is gone. But it endures into the present. Until we agree our future it will always be difficult to agree about our past. It is contested because the future is contested. This is the 40th anniversary of the 1981 hunger strikes. Those of us who supported the prisoners, in this case the Armagh women and the blanket men, have our view about what happened at that time and why. Jaz McCann has provided everyone with a highly personal account of what that meant to him and what was done to him and what he did during his seventeen years in prison including five years on the blanket protest. No words of mine can convey the awfulness of life on the blanket. I considered reproducing extracts of Jaz’s words to give a sense of this to you but that may spoil the book or parts of it. To do it justice you have to read 6000 Days. I appeal to anyone remotely interested in this period, whatever your opinion to invest in a copy. And to read it.

Finally, as someone who was close to the hunger strikers and who remains in awe of them I have always been conscious of the fact that ten men died. Every one of them, including Frank Stagg and Michael Gaughan who died on hunger strikes in England, and their families, deserve the admiration and respect of everyone who admires courage. Bobby Sands was the leader in every conceivable way and the first to die. For that reason sometimes Bobby may appear to overshadow the others, particularly in the media or the popular mind. Bobby certainly wouldn’t want that. He was first among equals. So I was very moved at how Jaz lovingly describes his relationship with Joe McDonnell who died after 61 days on the stailc. I am sure other prisoners could write in the same way of the other lads who died. And those who survived. It is only right that every hunger striker and his family are remembered as Jaz remembers Joe and his clann. Go raibh maith agat, Jaz. Your stories of him made me cry.

How lucky are we who knew Bobby and Joe, Francie and Martin, Tom and Patsy, Mickey and Kevin, Raymond and Kieran. They were our golden generation of leaders and fighters, poets and patriots. Ordinary but extraordinary human beings. Jaz’s book and the tales he tells reminds me of a line from a Brian Moore song;

When all is said and done

You know freedom is won by those Croppies who would not lie down.

By Croppies who would not lie down.

Thank you, Jaz. Thanks also to the McCann family. Especially your parents and Marian.

-oo0oo-

Sean Napier

In the early seventies as war waged on the streets of Belfast a young Jim ‘Jaz’ McCann was just like any other young teenage lad: going to discos, chasing girls, listening to rock music and being footloose and fancy free. The world was at his feet and Jaz was destined to make a big impression upon it… no doubt about that.

He certainly did, but maybe not as he had planned. He had joined the IRA and his life as a Volunteer would take a dramatic turn in 1976. Jaz was arrested after a gun attack in South Belfast on an RUC officer, who was uninjured, but whose colleagues in the vicinity gave chase.

There is a poignant scene near the beginning of the book when Jaz looks out from his cell, while on remand in Crumlin Road Jail, to young pupils in the yard of nearby St Malachy’s College, his old school. He remembers as a schoolboy looking up at the jail with an eerie feeling, a foreboding almost, that he was destined to be imprisoned behind its walls.

Though sentenced to twenty-five years, Jaz’s war was not over. Far from it. The British government had withdrawn political status and the republican prisoners stated that they would not be criminalized by the administration. Thus began one of the most epic prison struggles in Irish history.

The administration had everything on its side: a huge prison staff who had no compunction about using violence, archaic prison rules which, for example, allowed punishments of bread and water, the use of solitary confinement, and the punitive withdrawal of every known right normally accorded prisoners, from the right to exercise and see the sky one hour a day, to have reading and writing material.

To its shame, much of the media, bar a few noble exceptions, repeated British government propaganda and its various ridiculous mantras which denied reality and denied the political nature of the prisoners and the conflict.

In the H-Blocks David was meeting Goliath head on and Jaz and his fellow POWs were on the front line.

Every day the prisoners challenged what they considered the barbarity and inhumanity of the prison. They had the greatest weapon of all, a clear conscience, incredible dedication and an unbreakable conviction in the morality of their cause. As Bobby Sands wrote in his poem, The Rhythm of Time:

It lights the dark of this prison cell,

It thunders forth its might,

It is ‘the undauntable thought’, my friend,

That thought that says, ‘I’m right!’

Jaz, of course, would be in the middle of it all, along with many others, and would bear witness to one of the greatest battle of wills between Irish prisoners and their British jailors, and would be involved in an unimaginable protest which was to captivate the world in the climacteric 1981 hunger strike. (His life would take another dramatic turn in 1983 when he escaped from the Blocks.)

He takes us through the minutia of life ‘on the blanket’; every day a battle, on the no wash protest, the intimate body searches, the horrific wing shifts (so graphically depicted in Steve McQueen’s film, Hunger).

I felt like I was reading an alternative version of Homer’s The Odyssey, except that Jaz’s story was real, as were the monsters and tormentors, and it took not ten but seventeen years for him to find his way home.

And to think that all this was happening just eight miles up the road from Belfast. You have to occasionally nip yourself to absorb that reality—of men entombed for years in cells which froze in winter and boiled in summer (when the maggots emerged from the piles of rotten food in the corner of the cell to crawl over the naked bodies of the prisoners).

Without doubt the author has given us a very lucid and clear insight into his living nightmare, in a style which is open and honest and at times extremely moving.

His descriptions of Joe McDonnell, who would later die after sixty one days on hunger strike, their friendship and comradeship makes for incredible, powerful writing. I’d heard stories about Joe McDonnell before and the reverence he commanded, but his big, warm personality comes alive in these pages. For Jaz, Joe was a ‘giant of a man’ who guided and led men in their darkest hours, a man who loved his comrades.

And, of course, the 1981 hunger strike haunts this book. Jaz personally knew many of the men who were to die, who were never to leave Long Kesh alive.

After the hunger strike ends the struggle for political status continues as the blanket men emerge from their cells, onto the wings, out into the yards. You can almost feel the power they wield. Jaz describes in brilliant detail, the tension, and nail-biting minute-by-minute timeline of the great escape of September 1983 when using tools from the workshops that were meant to symbolize their criminalization, the prisoners overpower the staff in H7 and take over the entire block.

It is hard to believe that Jaz is a first-time author. He puts you there in the cell, in the back of the food van with thirty-six others, driving towards the gates of freedom. He puts you in the historical driving seat.

When I speak to former prisoners who went through the political status protest in Armagh Women’s Prison or the in the H-Blocks, many are still emotionally connected to the memories of the place and how every single one of them has been scarred in one way or another.

Many still find it very hard to talk about the death of their comrades on hunger strike and so I am grateful that Jazz, in this book, has revisited that darkness, 1981, the big escape, the six thousand days of pain from which he emerged sane, a man standing tall.

Jaz was there.

About the friendships and comradeships forged in those days and darkest nights in the Blocks (described as ‘Hades’ by Bobby Sands in one of his poems), Jaz says, simply:

‘We were more than blanket men. We were brothers.’

Succinct. Brilliant.

-oo0oo-

Below is a page reproduced from the book, where Jaz describes in great detail the atmosphere during the escape from H7 on Sunday, 25 September 1983