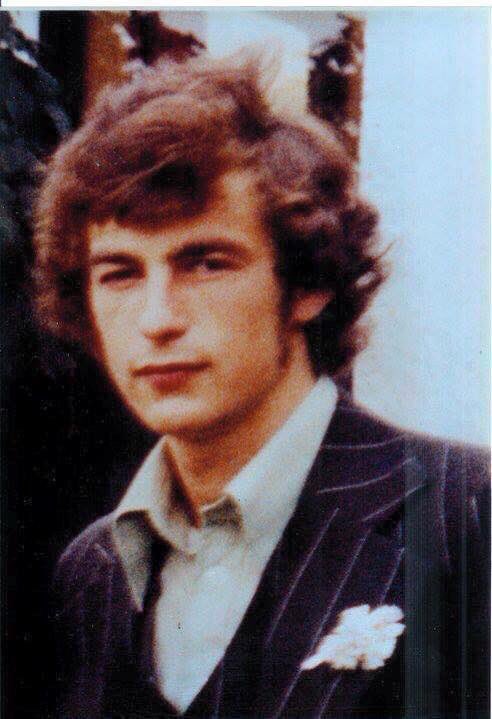

On Sunday, 7th August, the day before the 35th anniversary of the death of Thomas McElwee, people, some in period costume representing 1916, gathered in Bellaghy to pay their respects to the young 23-year-old who died on hunger strike after sixty two days. After a march through the town the commemoration was held just outside the gates of St Mary’s graveyard where both Thomas and his cousin Francis Hughes are buried.

On Sunday, 7th August, the day before the 35th anniversary of the death of Thomas McElwee, people, some in period costume representing 1916, gathered in Bellaghy to pay their respects to the young 23-year-old who died on hunger strike after sixty two days. After a march through the town the commemoration was held just outside the gates of St Mary’s graveyard where both Thomas and his cousin Francis Hughes are buried.

Excerpts from Padraig Pearse’s oration at the funeral of O’Donovan Rossa were enacted by Sean Kerr which was followed by personal reminiscences from Thomas’s friend and comrade, Colm Scullion, who was on active service with Thomas at the time of their arrest in October 1976.

“During the blanket protest,” said Colm, “Tom embraced the Irish language and education programmes conducted by, among others, Bobby Sands and Tommy McKearney. He actively took part in all debates and saw the necessity of politics side by side with armed struggle.

“Thomas was also was known as the hard man of the wing. The screws called him ‘Punchy McElwee’. He took no nonsense from them despite the vast odds. I remember the screws coming around with the dinner. One screw threw Thomas’s plate on the urine-covered floor. Thomas said nothing then punched him as hard as he could and he was punished with being sent to the boards for a month.

“Thomas was also a very devout Catholic. He never missed the Rosary and always carried the prayer books sent in by his mother, Alice. He was very anti-sectarian and expressed a wish to work among the Protestant community and show them that we could share this island as one people without English interference.

“Thomas joined the hunger strike on Monday 7th June. He was kept in our wing for about three weeks. The morning he left was terrible. He came to our cell door, we wished each other good luck. The men all got to their doors to bid him farewell. He walked up the wing to the gates and shouted, ‘All the best, Colm’.

“The screws then took him to the prison hospital in a van. We stood at our cell windows watching him wave out the window as we cheered and roared.

“That was the last time I saw ‘Big Tom’.”

Recalling 1981

Recalling 1981

Danny Morrison, the former Sinn Féin Director of Publicity, was the last speaker. He had given the oration at Thomas’s funeral in August 1981 and he recalled the hunger strike period. He said:

“In my experience the damage inflicted on us by the sectarian six-county state and the British occupation was compounded by partition and the Free Statism of the southern establishment. When RTE covered Bobby Sands going on hunger strike, or Thomas McElwee going on hunger strike what they covered was their Diplock court convictions.

“They never covered the men’s political or moral convictions because that would have gone against the desire to criminalise our struggle which was much easier to do than confront the power of Britain and British intransigence.

“1981 was the longest year in my life – but what must it have been like for the families of comrades dying a slow death?

“I do believe 1981 was ‘our 1916’. After 1981 all was changed utterly. After the Easter Rising, within a few weeks the British had executed the leaders, but here in the North the hunger strike deaths took place over a seven month period.

“In the middle of the hunger strike we thought a breakthrough was possible. We had been told that the British government was interested in settling it. I was allowed into the prison on Sunday 5th July to meet with the hunger strikers. I can still see those men around that table in the canteen of the hospital wing. On my left Kieran Doherty, then Kevin Lynch, then Thomas, Thomas McElwee, who by that stage had already completed 1,300 days in a H-Block cell on protest. Martin Hurson was too ill to attend. At the bottom of the table was Paddy Quinn. On the right was Laurence McKeown, then Micky Devine, then sitting beside me in a wheelchair was my old friend and comrade Joe McDonnell who would be dead within three days. They all spoke, including Tom who was adamant that their demands must be met.

“Just before the first hunger strike, in 1980, ended the British government was full of promises – that they would introduce an enlightened, progressive and liberal prison regime. But as soon as the hunger strike ended, and the pressure was off, the British reneged on their commitments, refused to budge and their bad faith triggered the second hunger strike.

“This experience of bad faith was what was foremost in the minds of the men around that table. They said they wanted to see what the British government was offering and they wanted it confirmed in a way that the British could not subsequently repudiate. The Irish Commission for Justice and Peace similarly asked the British to send in an official to explain what, if anything, was on offer.

“I left the hunger strikers to go to the doctor’s office where I was in telephone contact with Gerry Adams on the outside. He was liaising with Martin McGuinness who was liaising with Brendan Duddy the British contact. It was no way to do business and was open to misrepresentation and distortion. But as I was waiting to see what the British would say, a deputy governor, John Pepper, burst into the office and ordered me out and I never saw the hunger strikers again. The ICJP six times called upon the British to send in a representative to meet the prisoners but they never replied.

“After Joe’s death Michael Alison, the prisons minister, was asked to give the British position. He compared talking to hunger strikers as like talking to hijackers: ‘you continued talking while you figured out a way to defeat them,’ he said.

“And that was the policy that was to lead to the deaths of Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Tom McElwee and Micky Devine.

“I stood here 35 years ago and was honoured to give the oration at Tom’s funeral just as I am honoured to be here today in the presence of his noble family.

“Back then the British army and the RUC occupied and took up positions on surrounding roads. They were protected by not one but by six helicopters. Benny, who was also in prison on the blanket, arrived just in time from the H-Blocks on a 10-hour parole. Tom’s coffin was carried from the house by his sisters. At the end of the lane IRA Volunteers stepped forward and fired a volley of shots over his coffin.

“A piper played the H-Block song and many people quietly sang:

I am a proud young Irishman,

In Ulster’s hills my life began,

A happy boy through green fields ran

And I kept God’s and man’s laws.

“Among the mourners was Dinny Gleeson, a veteran of the War of Independence who had been in a Flying Column and had fought the British army and the Black and Tans – a real connection with 1916 and our long struggle for freedom.

“Chairing the graveside ceremony was veteran republican John Davey, who had been interned in the 1950s, 1960s and again in the 1970s. Indeed, it was in Long Kesh Internment Camp that he and I became friends. John himself was later to die in violent circumstances when he was assassinated coming from Council business to his home in Gulladuff.

“I wish to repeat what I said that day 35 years ago. Thomas McElwee was invincible from beginning to end, in life as well as in death.

“His dying words remain powerful and indeed were extremely prescient and are even more relevant today. Thomas said: ‘I bear no animosity, no ill-feeling towards anybody. I would like to live among the people… and promote peace and harmony among Catholics and Protestants and also with the British.’

“I have always found it remarkable that the oppressed are always more forgiving than their oppressors. It is very tempting to feel bitterness.

“The British were full of great spite and great cynicism. Their position was: ‘We know we cannot defeat you. But we will make sure you die.’

“I say they were cynical because not long after the hunger strike they conceded the five demands. When I was imprisoned in the H-Blocks some years later – and I see men here today whom I was with – I and those comrades had political status, prison conditions won for us by Thomas and his comrades.

“But the hunger strike was bigger than that. It inspired a new generation who put manners on the British, brought thousands more into republicanism, empowered the people, and created a political momentum which is unstoppable, a political movement in Sinn Féin which will un-partition Ireland.

“So we draw courage and great inspiration from Thomas McElwee and his example. He towers over the people who hunted him, arrested him, charged him, judged him, convicted him, stripped him, beat him, and the system that killed him.

“He towered over every one of them, and he was only twenty three.

“What a man.

“What a soldier.

“What a hero.

“What a son.

What a brother.

“Thomas McElwee.”