Read the Introduction to ‘Hunger Strike’, a book of essays published by the Bobby Sands Trust on the 25th anniversary of the 1981 hunger strike.

INTRODUCTION

By Danny Morrison

Many years after the ending of the hunger strikes and blanket protest a prison officer said:

“At first we thought they were dirty animals. The stench was incredible. Our stomachs turned when we went near the cells and we couldn’t understand how anyone could live in such filth. But eventually there was some grudging respect for those on the protest. They were incredibly determined. I didn’t agree with what they were doing but you had to admire them for sticking it out. At first I thought it would only last a few days, or a week or two at the most, but they kept going for years and then queued up to give their lives. I don’t think I would have been able to do it, no matter what the cause.”

[pp 256-257, ‘Inside The Maze – The Untold Story of the Northern Ireland Prison Service’ by Chris Ryder. Methuen 2000. ISBN 0 413 75240 2]

The blanket protest lasted for five years; the no-wash/no slop-out or ‘dirty’ protest for three years; the first hunger strike for 53 days; and the second hunger strike, when ten prisoners died, an incredible seven months.

Kieran Nugent, from Belfast, was the first republican prisoner sentenced and sent to the new H-Blocks. He was stripped naked, refused to put on the uniform and was beaten. His mattress and bedding were removed. The only thing in the cell was a blanket which he draped over his shoulder and thus began the blanket protest. On one occasion, the governor came into his cell and said, “We are going to break you.” Nugent recalled: “He stood there shouting at me. Gave me a slap in the face and then he stood back and watched the other warders beat me up.”

Over the years Nugent was joined by hundreds of others. In 1978 the prisoners began the no-wash/no slop-out protest which was to last until 1 March 1981, the day that Bobby Sands began his hunger strike.

Throughout the protest the prisoners suffered a variety of beatings, brutal anal searches whilst forced to squat over a mirror, solitary confinement, periods on a ‘Number 1’ bread and water diet (ruled to be illegal by the European Court of Human Rights) and loss of remission for each day on protest. Punishments also included loss of visits, letters, parcels, exercise, association and recreation, access to newspapers, magazines, books and radios. Each cell was supplied with The Bible. In the cold weather the prisoners stood on it to insulate their feet from the bare floor. They also wrote communications (known as ‘comms’), and Bobby Sands some of his poetry, on the margins of the Bibles’ fine Indian paper and on rice (cigarette) paper which folded small and was ideal for smuggling. Sometimes they smoked leaves from the Bible when they had no papers in which to roll their contraband tobacco. The prisoners defied the authorities and secreted pens, papers, tobacco and even small crystal set radios, inside their own bodies.

The first major breakthrough in highlighting the conditions came after Archbishop Tomás Ó Fiaich’s visit in August 1978. He said he was shocked by “the inhuman conditions” and that “one would hardly allow an animal to remain in such conditions, let alone a human being. The nearest approach to it that I have seen was the spectacle of hundreds of homeless people living in sewer-pipes in the slums of Calcutta… From talking to them it is evident that they intend to continue their protest indefinitely and it seems they prefer to face death rather than submit to being classed as criminals. Anyone with the least knowledge of Irish history knows how deeply rooted this attitude is in our country’s past.”

The British were unmoved and condemned Ó Fiaich’s comments.

Few in public life in Ireland, few journalists, artists, writers or poets, could claim ignorance of the H-Blocks after Archbishop Ó Fiaich’s visit to the jail.

Yet, little or no investigative journalism about developments in the northern prisons came out of the state broadcasting organisation, RTE. Proposed inquiries were throttled at birth and the rigid application of state censorship under which republicans were banned from radio and television was policed by a powerful clique of revisionists, associated with the almost now defunct Workers Party. There was literally such a climate of intimidation that few journalists dissented from the orthodoxy: ‘IRA evil/Brits good/unionists misunderstood’.

Within the British media a few conscientious journalists, to their credit, probed the abuses in the interrogation centres; made programmes about the H-Blocks; the RUC’s shoot-to-kill policy; challenged Thatcher’s (1988) broadcasting ban; and eventually examined collusion between British forces in the North and their surrogates in loyalist paramilitary organisations.

What was the response of Irish artists, writers and poets (Shelley’s ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’) to the imagery of “people living in sewer-pipes in the slums of Calcutta”?

By and large, a deafening silence, a blank canvas.

In ‘Warrenpoint’, the critic Denis Donoghue satirically notes: “Nationalism is a fine flower, so long as it grows in Israel, Tibet, Poland and Lithuania.”

His observation was a censure of the revisionists and those whose passion for human rights or national liberation is in direct proportion to the distance oppression is from home, the farther the revolutionary struggle is from Ireland.

Bobby Sands in his poems was even more critical, asking where were those in society who were meant to uphold or express in culture some defence of the oppressed? Many of them were more than eloquent when it came to condemning the IRA. But somehow they lost their voices when it came to condemning British violence and the brutality within the interrogation centres which were the first part of the conveyor belt, leading to the Diplock Courts and then the H-Blocks. He wrote:

The Men of Art have lost their heart,

They dream within their dreams.

Their magic sold for price of gold

Amidst a people’s screams.

They sketch the moon and capture bloom

With genius, so they say.

But n’er they sketch the quaking wretch

Who lies in Castlereagh.

The poet’s word is sweet as bird,

Romantic’s tale and prose.

Of stars above and gentle love

And fragrant breeze that blows.

But write they not a single jot

Of beauty tortured sore.

Don’t wonder why such men can lie,

For poets are no more.

They simply sat on or sniped from the fence while throwing their hands up in theatrical despair at the ‘intransigence’ of all sides. This was disingenuous: it was the prisoners who were defenceless and had their backs to the wall – not Thatcher.

Thus it was an honourable minority of artists, writers and poets that bore witness.

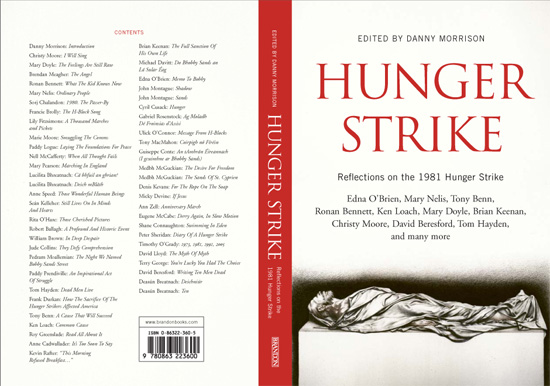

Musicians like Christy Moore, Donal Lunny, the band Moving Hearts, balladeers like the Wolfe Tones, artists like Bobby Ballagh, actors like Stephen Rea, and a small number of other musicians, poets and writers were there ‘before’ and ‘after’. Ballagh’s 1980 image of, prophetically, a dead blanket man on a mortuary slab (on our cover) was first used on the cover of Tim Pat Coogan’s book, ‘On The Blanket’, which was itself an important contribution to raising public awareness about the protest.

There were, of course, mainstream works written during or informed by this grim period, and published later.

A discussion of sorts about the role or responsibility of the poet in a conflict situation arises in Seamus Heaney’s ‘Station Island’ (1984) when the poet self-consciously struggles with a sense of guilt. It is a narrative about a pilgrimage to Lough Derg – St Patrick’s Purgatory – where the poet fasts (a metaphor for hunger-striking) and meditates.

Like Dante’s wanderings through Hell and Purgatory, disparate souls address the poet.

(The resonances are actually quite powerful because in ‘The Divine Comedy’ one of those to address Dante is the spirit of Count Ugolino, who had fought for the sovereignty of Pisa. In 1289, in the month of March, which also happens to be the month when Bobby Sands began his hunger strike, Ugolino was arrested and thrown into prison along with his two sons and grandsons. The door was sealed; they were deprived of food and starved to death.)

In ‘Station Island’ the ghost of a friend of the poet, a shopkeeper (presumably, William Strathearn) who was assassinated by loyalists, addresses him. A dead hunger striker (presumably, Francis Hughes) also makes an apparition, as does that famous but unnamed self-exile James Joyce.

To Strathearn, the poet apologises:

“Forgive the way I have lived indifferent –

forgive my timid circumspect involvement.”

He is told there is nothing to forgive – which must be very reassuring.

Francis Hughes describes his slow death, how his blanket protest is like a transcendental ambush. But Heaney associates his death with decay; there is nothing life-affirming about his sacrifice. Those responsible for Hughes’ predicament, and the objective of Hughes’ hunger strike (which can be depoliticised into a demand for dignity), are not referred to. Instead, the poet thrashes out:

“‘I hate how quick I was to know my place.

I hate where I was born, hate everything

That made me biddable and unforthcoming’”.

Like Dante’s ascent from Hell, Heaney is slowly rising… to an important conclusion. Joyce tells him:

“‘Your obligation

is not discharged by any common rite.

What you must do must be done on your own

…

“‘let others wear the sackcloth and the ashes…

“‘That subject people stuff is a cod’s game,

infantile, like your peasant pilgrimage.’”

Shriven and advised by Joyce the poet breathes a sigh of relief. But back in that real, other world from which Heaney hailed, Ian Paisley, twenty five years later, still demands that republicans be forced to wear the sackcloth and ashes in public.

The protests which began in the H-Blocks and Armagh Women’s Prison in the autumn of 1976 were caused by the British government reneging on an agreement it had made in 1972 about the status of prisoners convicted in relation to the conflict.

The reason why republicans were in jail was because of the armed struggle in the North. It had grown out of the failure of the civil rights movement, and as a reaction to both the violence of the unionist government and British rule in support of the union. The objective of republicans was Irish independence and they viewed their struggle as a continuation of the fight for freedom which had been subverted by the partition of Ireland in 1921.

The vast majority of the prisoners were young, in their late teens and mid-twenties; were Volunteers of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), sympathisers or supporters of the IRA; while others belonged to the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA).

After the conflict broke out in the North in the early 1970s, arrests and prosecutions led to an exponential growth in the number of convicted republicans held in Belfast Prison (Crumlin Road jail). When these arrests failed to stem the IRA campaign the British government in August 1971 introduced internment without trial, exclusively against the nationalist community, despite violence from loyalists. Hundreds of republican suspects were imprisoned in various jails. These included a converted ship, the Maidstone, anchored in Lough Neagh; a former RAF base called The Long Kesh, eight miles from Belfast; and Crumlin Road jail itself.

The internees were not required to do menial prison work or wear prison garb – grey denim trousers and jacket, black boots, blue and white striped shirt. They were not regimented by the prison authorities, nor obeyed commands according to a prison number, but organised and supervised their own daily regime. They had more rights than sentenced prisoners but they had no release dates and were subjected to regular aggressive military searches. They slept on bunk beds in Nissen huts, situated in barbed-wire enclosed cages (which the authorities called ‘compounds’). In fact, they had something equivalent to prisoner-of-war or political status.

Using the leverage of this anomaly – two sets of republican prisoners being treated in different ways – the sentenced republican prisoners in Crumlin Road went on hunger strike in May 1972 demanding political status.

After thirty-five days into the strike and before there were any deaths the British conceded ‘special category status’, which was political status in all but name. The republican prisoners, numbering around eighty, including those in Armagh Women’s prison, and about forty convicted loyalists who also benefited, were allowed to organise themselves in the same way as the internees. The sentenced prisoners in Crumlin Road jail were eventually moved to their own cages in a section of Long Kesh Camp, where their numbers swelled to several hundreds over the years.

The British army was responsible for the security around the outside of Long Kesh. Soldiers and guard dogs patrolled the perimeter of the cages and soldiers in watch towers monitored the activities of the prisoners. There were also regular searches by prison staff, supported by the military, for tunnels and tools of escape. The huts within each cage were locked by prison staff at night and unlocked each morning. Magilligan Prison in County Derry had a similar lay-out and regime. Female internees and sentenced prisoners in Armagh had political status but were held in traditional cell blocks. Within the jails the republican prisoners, who considered themselves as revolutionaries and part of a guerrilla army, used their time to educate themselves and studied history, politics, literature and languages.

In the Twenty-Six-Counties the Offences Against The State Act, authorising the use of non-jury courts, was re-enacted in 1972 as part of the crackdown on the IRA and its supporters. Those convicted once again organised republican structures within the jails, planned escapes, and organised education classes. One IRA prisoner, Tom Smith, was shot dead attempting to escape from Portlaoise Prison in 1975. Often, there were confrontations between inmates and the authorities over prison conditions. However, successive governments never attempted to criminalise the prisoners in the way, for example, it had been tried in the 1940s when prisoners resisted and died on hunger and thirst strike. Republican prisoners were not required to wear a prison uniform and could associate with each other as a defined group.

Within Britain itself – where there was no internment – republican prisoners were initially small in number, were badly mistreated and often the victims of racist beatings and intimidation. Later, when they were better organised and relatively stronger in number they were segregated from the general prison population in special control units. But in those early days there were several hunger strikes, mostly around the demand for repatriation to a prison closer to home. Two republican prisoners were to die on hunger strike: Michael Gaughan in June 1974 and Frank Stagg (on his fourth hunger strike) in February 1976.

By granting political status in 1972 the British government settled the prisons in the North for a while. However, the powerful image of Long Kesh as a PoW camp irked British politicians and contradicted their government’s propaganda. Ministers depicted the IRA’s campaign as ‘terrorism’, which had no justification, no mandate and no support.

But to outside observers Britain was imprisoning captured enemy combatants with a status that suggested some legitimacy (and also occasionally engaged in secret contacts and explorative talks with the IRA and/or its perceived political wing). The observers also noted that British propaganda was no different from that used by British administrations dealing with national liberation organisations and insurgencies in colonial confrontations throughout the former empire. When it became expedient the renowned ‘terrorist’ leaders would, no doubt, be welcome in No 10 Downing Street as statesmen.

In 1975/76 the British government launched a major three-pronged offensive.

Under ‘Ulsterisation’ it began scaling down the numbers of British troops deployed in the North. Fewer troops in the firing line meant fewer British army fatalities which in turn helped stem any domestic, anti-war or troops out sentiment (which the IRA had hoped its campaign would generate). Troops were replaced by members of the local Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). Predictable, increased casualties among the RUC and UDR, whose members were overwhelmingly drawn from the unionist community, allowed Britain to depict the conflict as sectarian, the ‘Catholic IRA’ killing the ‘Protestant RUC’ with Britain as ‘honest broker’ acting to keep apart the two ‘warring, religious communities’.

Under ‘Normalisation’ the RUC was to be delegated primacy in security matters. In other words, the situation was to be presented as a difficult ‘policing’ problem. Simultaneously, the British pushed for increased talks between the constitutional political parties to agree upon that elusive objective – devolution and an ‘internal solution’.

In preparation for the third prong of this offensive, ‘Criminalisation’, British ministers began to claim that the nature of the conflict had changed. ‘Godfathers of violence’ were now ‘lining their own pockets’ and the IRA was ‘masterminding a criminal conspiracy’.

Editorial and feature writers, particularly in the North, took the cue – and took sides. Without question they adopted and echoed every phrase uttered by direct rule ministers.

The Emergency Provisions Act, which allowed for non-jury, single-judge Diplock Court trials, became central to the new offensive. The burden of proof was now shifted to the accused who had to prove his or her innocence, and statements (most of which were obtained by ill-treatment) became admissible as evidence. Most of these statements were taken in special interrogation centres by a select group of eighty RUC detectives. Indeed, up to 80% of all convictions were subsequently based on self-incriminating statements made by prisoners, many of whom were beaten during interrogation. It was years before campaigns by human rights organisations successfully highlighted and exposed these abuses.

In 1975 Long Kesh Prison (which the British had earlier renamed ‘The Maze’) was expanded, with a wall dividing the old from the new. Eight new prison blocks designed in the shape of an ‘H’, with four wings containing up to 26 cells in each and an administrative area joining them, were built.

The government announced that anyone arrested for a scheduled offence (a wide range of defined activities related to subversion) from 1 March 1976 would be considered a criminal and would be sent to the new regime in the H-Blocks or to Armagh women’s prison without political status.

There was a major contradiction in the British position in that Section 31 of the Emergency Provisions Act (and, later, the Prevention of Terrorism Act) defined scheduled offences and ‘terrorism’ as “the use of violence for political ends” (my italics).

After having been arrested under special laws, been questioned in special interrogation centres, been tried in special courts with special rules of evidence, the prisoners were told when they arrived at the specially-built H-Blocks there was nothing ‘special’ about them.

Even with political status life in prison was harsh. At times of major tension in the jail or after specific confrontations the IRA and loyalist paramilitaries threatened some prison officers and carried out some attacks. But up until 1976 no prison officer had been killed as a result of working in the prisons. In the main, prison officers were not singled out by the IRA for attack. In 1974, after the cages of Long Kesh were burned down by republican prisoners, the British army shot dead an internee, Hugh Coney, who was trying to escape. And other prisoners died through medical neglect as a result of prison staff not responding to emergency calls.

But it was not until April 1976 – a month after the withdrawal of political status – that the first prison officer, Patrick Dillon, died at the hands of the IRA. During the protest one third of the prison officers who worked in the H-Blocks had been brought in from Britain on special bounties, and most of them were former servicemen.

Although Britain was to eventually fail in its objective of forcing the prisoners to accept criminal status it was not before a heavy price was paid. Those who suffered were the prisoners, their families, protestors and civilians on the outside (including children and a mother killed by plastic bullets, and a milkman and his son whose vehicle crashed into a lamppost during a nationalist riot), and prison officers and their families. All of them were caught up in a clash of wills which one governor was later to describe as “a battle for the false aim of criminalisation that was always going to fail.”

Even the IRA’s chief opponents within the British army privately rejected the notion that the IRA was ‘a criminal conspiracy’ without support. Writing a secret assessment of the IRA in 1978 Brigadier James Glover, the most senior army officer on the Defence Intelligence Staff, stated that the IRA was representative of the nationalist working class, “of which they [Volunteers] form a substantial part [and] do not fit the stereotype of criminality which the authorities have from time to time attempted to attach to them.”

A few months after the blanket protest began their families formed Relatives Action Committees (which Mary Nelis describes). Later, a National H-Block/Armagh solidarity committee rallied in support of political status. Leading members of this committee were assassinated by loyalists, more than likely in collusion with British forces, given what we know now.

The prisoners set out five demands. These were:

The right to wear their own clothes.

The right to abstain from penal labour.

The right to free association.

The right to educational and recreational facilities.

Restoration of lost remission as a result of the protest.

The Labour government, which had introduced criminalisation, was replaced by the Conservatives under their leader, the implacable Margaret Thatcher, in 1979.

In 1980 the IRA publicly called a halt to its reprisals against prison officers to facilitate mediation attempts by the all-Ireland primate, Cardinal O Fiaich. However, after several months of talks the British government refused to budge and thus began the 1980 hunger strike by seven prisoners.

It lasted 53 days. During it there was a marked increase in the mobilisation of public support. Thousands demonstrated throughout Ireland. Many public figures were forced to respond. Some, including the Irish government, adopted the stance that it was difficult if not impossible for Thatcher to act under pressure. If the prisoners would only end their fast the government would put pressure on the British to change its policy.

The hunger strike ended dramatically on December 18. It was called off to save the life of Sean McKenna who was close to death, at a time when the British became involved in secret contacts with the republican leadership, stating that they sought a resolution. A British representative (code named ‘Mountain Climber’) supplied a document to Fr Brendan Meagher (code named ‘the Angel’) at a meeting in Belfast’s International Airport (which Meagher describes here).

The British side promised to progressively introduce a liberal prison regime. However, as soon as the hunger strike ended, they reneged and the ‘concerned’ politicians all but disappeared, some smug with the impression that the morale of the protestors and the back of the protest had been broken. The administration insisted that the prisoners must wear prison-issue clothing.

Mary Doyle, herself a hunger striker in 1980, writes about the anger and frustration the prisoners felt.

And so, the prisoners announced a second hunger strike, led by Bobby Sands.

In the political literature of the period and in media references Bobby Sands’ name tends to overshadow his nine comrades. (Some of the writers in this book refer to Bobby Sands’ name being raised by a prisoner facing a death sentence in the Philippines, by a PLO teenager on the streets of West Beirut, and by a Russian at the grave of Ezra Pound in Venice. ANC prisoners on Robben Island when planning a hunger strike used the expression “doing a Sands.”)

Bobby’s name is highlighted for many reasons. He was a jail veteran, already a well-established leader and prison spokesperson. He was a writer and a poet. He devised the strategy of the staggered hunger strike. He became MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone in that extraordinary by-election. He was the first to die at a time when the international coverage was at its height, and his iconographic image, that smile, that long flowing hair, became instantly recognisable, like Che Guevara’s.

But in the counties, the local areas, the home places, the townlands and streets of the other hunger strikers, each local hunger striker – Francis, Raymond, Patsy, Joe, Martin, Kevin, Kieran, Tom and Micky – is immortalised on the lips of old and young alike, and a fierce pride in the memory of each man and the detail of each man’s life is passed down the generations.

During the hunger strike there were many attempts at mediation, including one by the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace in July 1981. This occurred at a time when the British were again in touch with the Republican Movement through ‘a back channel’. While the British representative suggested there could be a settlement those responsible for prisons refused to put the details of the offer formally to the prisoners and in a way that was verifiable. No deal thus emerged.

The hunger strike continued but as a weapon was neutered by relatives of the strikers who increasingly began authorising medical intervention once the prisoners lapsed into a coma. Terry George, who made the film ‘Some Mother’s Son’ on this sensitive subject, describes what influenced him and how he brought his work to the screen.

The prisoners ended the hunger strike on 3 October 1981. Within two weeks the British conceded their right to wear their own clothes. The prisoners were united and organised and fought on for the rest of their demands through sabotaging the workshops and using their numbers to establish segregation.

Within two years the prisoners had political status and the IRA command structure within the jail was recognised by the administration. In the words of a former governor, they (the prison authorities) “learned at a terrible price that you could only run a prison like the Maze with prisoners like that with their consent.”

The final admission of the political nature of the prisoners was their early release under the 1998 Belfast Agreement.

Twenty five years after their deaths on hunger strike the sacrifices of those ten prisoners, and that of their comrades, in the H-Blocks and in Armagh Jail, continue to have an impact in Ireland and further afield.

Certainly the hunger strike’s most initial tangible effects were to re-energise and increase support for the Republican Movement, and inspire many people to join the IRA and Sinn Fein. The stupidity of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s depiction of the hunger strike as “the IRA’s last card” was there for the world to see, though not understood by her herself.

Until 1981 republicans were highly suspicious of electoral politics, with good reason given the history of splits on the issue, particularly on the subject of abstentionism. Electoral politics, they felt, were synonymous with constitutional politics. Were it not for the elections of Bobby Sands to Westminster and Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew to Leinster House it is doubtful if Sinn Fein could have made its transition to embracing electoralism so smoothly. The election of Kieran Nugent and Paddy Agnew broke single party dominance of Leinster House by a Fianna Fail government and ushered in the era of coalition governments.

For northern nationalists 1981 set in train a growing confidence which had been absent before that period. Today, nationalist morale is buoyant despite the protracted nature of the peace process and many disappointments.

Former prisoners, blanket men, surviving hunger strikers and escapees went on to become Sinn Fein negotiators and in impressive numbers were elected to office at council level, to the northern Assembly and to the Dail. In the near future they will in all likelihood be represented in two increasingly interdependent administrations covering all Ireland, if not in the long term in a government of a unitary Ireland.

Throughout 2006, young people – who were not even born in 1981 – flocked to various exhibitions, discussions, debates and lectures held across Ireland to commemorate what for many is the historic event of the North since the foundation of the state in 1921. Indeed, many republicans refer to the hunger strike as their ‘1916’. The hunger strike remains of enduring interest to Irish people, historians, political analysts and students (it has entered the curriculum as a major study). Several books about the period have been published, including a new biography on Bobby Sands by Denis O’Hearn, ‘Nothing But An Unfinished Song’, and, of course, ‘Ten Men Dead’ by David Beresford, first published almost twenty years ago, continues to sell and has never been out of print. Here, Beresford tells of how he came to write that book which has been described as the definitive account of the hunger strikes.

To mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the hunger strike the Bobby Sands Trust decided to invite a variety of writers, poets, journalists, musicians, activists, critics, filmmakers, playwrights, and broadcasters to reflect on 1981.

The choice was deliberate – to give the book a distinctive literary flavour. I would like to thank the contributors (forty-nine!) who all gave their services for free. Some were/are activists. Some, like the writer Eugene McCabe, are pacifists. Bill Brown gives a perspective from the unionist community, Pedram Moallemian as a teenager in Tehran watching events unfold in Belfast.

I look back at 1981 with extreme sadness but with astonishment at the epic nature of that prison struggle and at the courage of those men and women.

The British government, the RUC, the courts, the prison administration thought it could criminalise my generation of republican patriots by breaking the prisoners.

They took away their freedom, then their clothes, shoes and socks and locked them up for twenty-three hours a day. Then they took away the walk around the prison yard in fresh air, under blue skies. They took away their smokes – that small precious allowance of tobacco which in every prison steadies and calms nerves and makes the day endurable. They took away their beds. When this didn’t break them they took away the light that streamed through the window. They took away the space under the door. They took away the sound of music, poetry books and literature, photographs of loved ones, letters home, their visits… their very lives.

Leaving them with nothing.

Or so they thought.

Danny Morrison, Belfast, 5 May 2006