The creative and productive use of the former Belfast Prison on the Crumlin Road, which has been the venue for filming, dramas and tours [see Jim Gibney ‘Irish News’ article below], is on display once again this week with an exhibition that runs until Saturday, 26th April.

‘Belfast in the 1950s’ is the latest in a series of exhibitions, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, and organised by Glenravel Local History Project, which have been looking at different decades from the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s (including an extensive section of the Belfast Blitz) and now this new one looks at the 1950s. The venues for these have ranged from the Waterfront Hall to the Freemasons’ Hall in Cornmarket and this one continues with the places of interest this time being the Belfast Prison on the Crumlin Road.

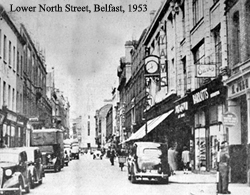

This massive collection of photographs will look at numerous streets, places, buildings, events and of course people. The exhibition will also consist off cinema listings, maps of every area of Belfast in 1955 and front page newspaper reports ranging from the disasters such as the sinking of the Princess Victoria and the Nutt’s Corner plane crash right through to the infamous Patricia Curran murder [the subject of an excellent novel ‘Blue Tango’ by Eoin McNamee]. The whole exhibition promises to be a marvellous insight to 1950s Belfast to all who visit.

Also on display will be photographs showing the food we ate, the sweets we scoffed, the comics we read, the toys we played with and the advertisements we read including the infamous work-out kit after having sand kicked in your face.

Also available will be publications based on the exhibition which will contain all the photographs on display.

This exhibition not only promises to bring back hundreds of memories for those who remember the period but also promises to be fascinating for those who don’t.

Rita Harkin, member of the Heritage Lottery Fund Committee, said: “By collecting, displaying and interpreting these photographs, the ‘Snapshots of Belfast’ project provides a real insight into our social and cultural heritage. This current exhibition features the people, places, objects and events of the period to bring 1950s Belfast to life, and we are delighted to be involved.”

For more information contact Joe Baker on [028] 9074 2255

*****************************************************************************************************************

Long Kesh Could Be A ‘Must See’ Attraction

by Jim Gibney [Irish News, 23rd April, 2009]

There is a portrait of Tom Williams hanging in the Roddy’s Social Club in West Belfast. It was painted by a former political prisoner Frank Quigley – a Falls Road republican.

The portrait shows Tom Williams in the summer of his youth: a mop of brown curly hair sitting atop a broad, attractive, smiling boyish face. He is slightly hunched over leaning into the portrait; he is wearing braces and an open-neck collarless cream coloured shirt. What today is fashionably called a granddad’s shirt.

The engaging portrait puts a face to a legend which has been around republican politics since the hangman, Pierrepoint, put a noose around Tom William’s 19 year old neck in September 1942.

A fortnight ago I spent a few minutes in the condemned cell where Tom Williams spent the last days of his life and experienced the spine-chilling sound of the trap door through which the young man fell when he was hanged, as a mock execution was enacted by our prison guide.

I was accompanied on the tour of Crumlin Road prison by a friend Chris Simpson. His grandfather Pat was part of the IRA unit who were sentenced with Tom Williams to be hanged for the killing of RUC Constable Patrick Murphy. Chris stood in the cell where his grandfather, as a teenager, was held awaiting execution before the sentenced was commuted.

Also in the tour group was Paul Butler. A Sinn Fein MLA, Paul was in the Crum, as it is known, for eight months in 1974 as a seventeen year old. He later served 15 years of a life sentence.

Also with us was my brother Damian who knew the Crum from the outside through visiting me, his daughter Sinead who as a child also visited me and her boyfriend Neil and a lawyer from the US, John Kennedy, a relative of the famous Kennedy clan.

Belfast’s Crumlin Road Prison is not only an impressive, indeed, imposing, example of Victorian prison architecture it is also a museum, an artefact in its own right.

The Office of the First and Deputy First Minister and the North Belfast Community Action Unit collaborated to ensure that the prison – now closed after 150 years as a penal institution – and the nearby former British military base, Girdwood Barracks, are the centre-piece of a plan to rejuvenate north Belfast.

The prison has been re-opened as a tourist attraction and in the first few months after it was opened last year attracted 5,000 visitors – a clear sign that the decision to list and open the prison to the public is popular.

Built long before partition the history of the prison reflects the social, political and economic history of this island over a century and a half as well as the changes in penal conditions.

Victims of the famine were held there as were children; suffragettes campaigning for votes for women; thousands of political prisoners; and seventeen men were executed and buried in its grounds.

The ten hunger strikers who died in 1981 were held there on remand as was Eamon de Valera, Ian Paisley senior, David Ervine, Gusty Spence, Gerry Adams, Martin McGuinness, Gerry Kelly and Mayor Tom Hartley, among others.

Dozens of daring successful and not so successful escapes took place.

Tours of the prison can be booked online or by phoning the Belfast Visitor and Convention Bureau. The prison is promoted as a ‘must see’ destination by those involved in tourism and rightly so.

What I find incredible is that a similar project with similar appeal and potential a few miles outside Belfast at Long Kesh has been dogged by unionist opposition yet the rightly ambitious project centred on the Crum has been advanced practically without a whimper of protest from unionists, including the MP for the area Nigel Dodds.

The plan to build at Long Kesh a multi-sports stadium for Gaelic football, soccer and rugby alongside the preserved prison buildings, including the prison hospital where the hunger strikers died, and a conflict transformation centre, could have become a national and international symbol of peace and reconciliation on this island.

But it was scuppered by power struggles, petty mindedness, and personal intrigue inside the DUP.

But just like the Crum the prison buildings at Long Kesh are listed, and will be developed.